|

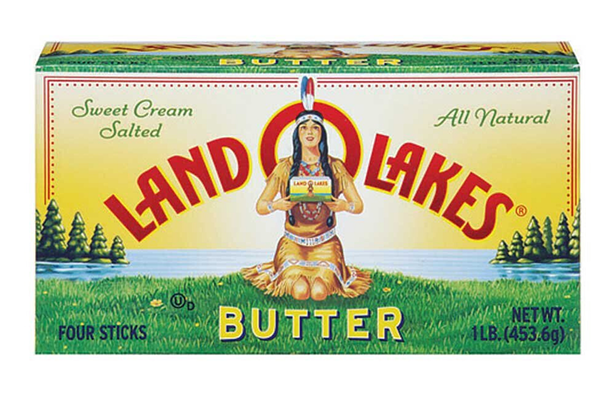

Land O’ Lakes has removed the Indian woman from the cover of its butter packaging that Ojibwe artist Patrick DesJarlait reimaged in the 1950s. Note: Article originally published The Circle Newspaper on May 5, 2020 By Robert Desjarlait It wasn’t noticed until April that the Land O’ Lakes iconic image of the Indian Maiden, Mia, was missing. The disappearance of the iconic image was lost amid in the developing outbreak of coronavirus in February. It wasn’t until an article appeared in Minnesota Reformer by Max Nesterak that people took notice. The news of Mia’s demise appeared in national news including the New York Times, New York Post, Star Tribune, Time Magazine, National Review, Indian Country Today among others. And with it came the controversy of the image itself – was it the elimination of a stereotype? Or was it the loss of an image that many Natives felt connected to? Suzan Harjo, a well-known Native American rights advocate, said that Patrick DesJarlait’s “stereotype of an ‘Indian’ woman is not illustrative or even in the vicinity of his good work.” Harjo’s dismissal of DesJarlait’s skill as a commercial artist overlooks the civil rights barriers he overcame to establish himself in an art world dominated by white advertising executives and artists. Fresh out of Pipestone Boarding School in Minnesota, he joined the Navy in 1942 and was stationed at the Poston, also called the Colorado River War Location Center, for Japanese internees. He organized a sign and art department as a source of recreation for internees. He was then transferred to San Diego where he worked in the Naval Visual Aids Department producing brochures and promotional films. He worked alongside animation artists from Walt Disney and MGM studios. In the evenings and weekends, he honed his skills as a fine artist. After he returned home with an honorable discharge, he moved to the Twin Cities. He worked as a staff artist at Reid H. Ray Films which, at that time, was the oldest commercial motion picture company in the U.S. He worked at several Twin Cities film companies and advertising agencies including Campbell-Mithun Advertising, where he created the Hamm’s Bear, animated Smokey the Bear, and was part of the creation process for the Minnegasco maiden, the Firebird for Standard Gas, and Mia, the Land O’Lakes maiden. Mia was created in 1928 by Brown & Bigelow illustrator Arthur C. Hanson. She was depicted kneeling, in profile, on a wooded lakeshore. In 1939, artist Jess Betlach changed her position to kneeling toward the viewer, holding the butter box, on a farm field with cows and a lake in the distance. In the 1950s, DesJarlait reimaged Mia. He made her features softer and added Ojibwe floral motifs to her regalia. He eliminated the farm field and put a lake behind her with two forested points of land. Anyone who is familiar with his art would recognize the Narrows at Ponemah where Lower Red Lake and Upper Red Lake meet. It was a motif he used often in his paintings. He placed Mia’s head within the “O” of the brand name, lending an iconographic image to subliminally enhance the beauty of Native womanhood. But his iconic imagery became lost and forgotten in the era of political correctness. Antimascot advocates applauded her disappearance from the label. According to North Dakota Rep. Ruth Buffalo, the Land O’ Lakes maiden went “hand-in-hand with human and sex trafficking of our women and girls….it’s a good thing for the company to remove the image.” But some saw it differently. Dan McLaughlin (National Review) said, “Color me skeptical that butter labels have any effect on sex trafficking.” McLaughlin added, “The new packaging no longer has any Native American connection, and erases the work of a Native American illustrator.” Govinda Budrow is on the faculty of Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College in Cloquet. She says different generations have different relationships with the image. “I know from my mother’s generation especially, it represented basically the only representation that she had. It was the one thing that smiled back at them to say, hey, other people exist like you and they are out there.” Budrow said that in disappearing without a trace, and with no one talking about it, Mia has become more like a contemporary Native woman than ever before. “It just seemed way too ironic when I was thinking about this, about how things happen to indigenous women even now today, where women are being trafficked, they’re being oversexualized, they’re not being heard within spaces, are not being seen within spaces. And then they go missing and there’s nothing being said about them.” Budrow’s comments reflect the general trend on Facebook in which a majority of respondents, the majority of whom are Native women, posted stories about Mia that supported her existence. Indeed, for many, Mia provided them with a visual, tangible connection to their identities as Native women. In today’s politically correct world, Mia devolved into a demeaning stereotype. With her absence, the northern landscape, with its lake and forest, is devoid of her beauty. And, like a missing woman, she will be remembered to those to whom she brought comfort and a sense of grace. Robert DesJarlait is a citizen of the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation. He is an artist and writer. His father is Patrick DesJarlait. Robert DesJarlait is a citizen of the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation. He is an artist and writer. His father is Patrick DesJarlait

2 Comments

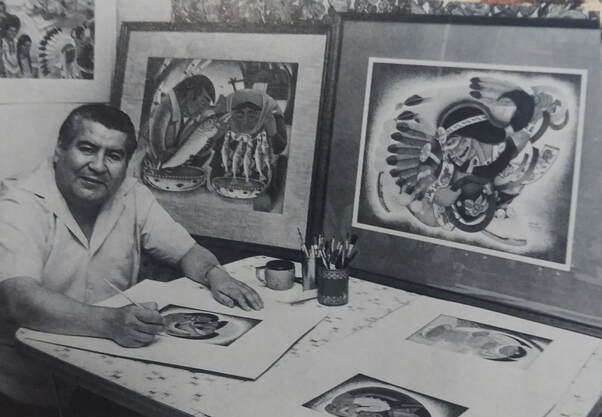

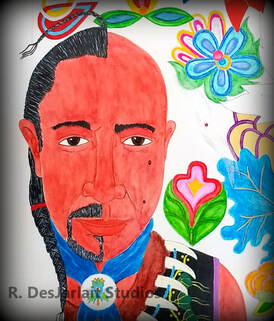

Red Lake Ojibwe artist Patrick DesJarlait circa 1971. (Photo courtesy of Robert DesJarlait) Dalton Walker

Indian Country Today There's more to this story than a box of butter. One version starts when Land O’Lakes quietly removed “Mia,” the face of its butter since 1928 from its boxes. Company president Beth Ford said in Feb. 6 news release that the new marketing campaign “needed packaging that reflects the foundation and heart of our 1/4 company culture - and nothing does that better than our farmer-owners whose milk is used to produce Land O’Lakes dairy products.” This was all done without fanfare. Where Mia kneeled for nearly a century, there is now an empty space. What remains is a logo and a lake with trees in the background. People picked up the new butter packages without much notice. Then the Minnesota Reformer, a digital nonprofit news source, reported the change on April 15. That story went viral and was posted by national media ranging from The New York Times to NBC’s Today show. The change was applauded by many in and out of Indian Country, including Minnesota Lt. Gov. Peggy Flanagan, White Earth Nation. “Thank you to Land O’Lakes for making this important and needed change,” Flanagan tweeted. “Native people are not mascots or logos. We are very much still here.” North Dakota state Rep. Ruth Buffalo, Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, told a Fargo Forum reporter that the image goes “hand-in-hand with human and sex trafficking of our women and girls … by depicting Native women as sex objects.” A week later Rep. Buffalo added on Facebook: “It is unfortunate the issue of Land O’ Lakes cooperative’s recent decision to phase out the ‘Mia the butter maiden’ logo on its packaging has been used in a divisive way. As an elected legislator in North Dakota and a Native American woman, I was asked for an opinion on this decision that was, as with most complex issues, distilled to a short quote.” Buffalo’s well-reasoned post explored issues ranging from using Native images in the multibillion advertising issue to the impact on popular culture. “We are not invisible people, and we no longer accept breadcrumbs or in this instance, butter for those breadcrumbs,” she concluded. “Let’s work together to make real, contemporary Native American women visible and value their work and contributions to today’s society. Let’s respect and value their voices even when we may disagree.” This is where the story twists because the legacy of Ojibwe artist Patrick DesJarlait goes well beyond Mia and Land O’Lakes. DesJarlait was employed by the advertising agency Campbell-Mithun in Minneapolis when he was given the assignment to market the farmer-owned cooperative. The original brand of “Mia” had been refurbished twice since its launch in 1928. DesJarlait was tapped to create a third version. He reimagined a more human character, adding detail to Mia’s face and floral motifs on her dress. Subtle changes that mattered. That was the brand that stuck for seven decades. But the real legacy of DesJarlait is his body of work, some 300 pieces of art across the U.S. in museums and private collections. For many, especially for Red Lake Ojibwe in Minnesota, DesJarlait’s artistry impact remains nearly 50 years after his death. The award-winning artist and U.S. Navy veteran died at age 51 in 1972 from cancer complications. “My dad’s artwork has been out there for so long, and there's so many people that just don’t even know about his beautiful artwork,” DesJarlait’s daughter Charmaine Branchaud said. “There’s a story behind that man. It’s a part of history. Now, we are making history again with Mia. She’s disappeared, but that doesn’t mean my dad’s artwork is going to disappear. She was just a little bitty part of it. He had a lot of accomplishments in his life.” DesJarlait’s son, Robert DesJarlait, 73, said he was initially glad that the stereotypical image was finally removed. Then, the power of social media reminded him of another side of the discussion that was overlooked. On his Facebook page, Robert said many Ojibwe people shared their perspective of Mia while growing up Native. “Basically, it was giving the previous generation a sense of almost empowerment to see a Native woman on a box of butter. It gave them a sense of cultural pride,” he said. “After seeing those posts, I said, ‘that’s right, that’s why my dad created this image to begin with’.” The design, besides Mia, shows a lake with two points of land that Robert DesJarlait said represented Red Lake and an area on the reservation known as the Narrows, where lower and upper Red Lake meet. Another homage, one that is hard to see on the products, on Mia’s dress are Ojibwe floral design patterns. My father was working it both ways - he was strengthening the Land O’Lakes name by placing Mia at the lake and he was integrating a deeper Ojibwe connection to the environment in which they lived. Trees and lakes are part of our identity. As such, his art, and Mia, was a visual reminder of our connection to our homelands,” Robert DesJarlait said in a Facebook post. Robert DesJarlait, who like his dad is an artist, said his father has never gotten the proper credit for his creations. In the early 1950s, Patrick DesJarlait created the bear mascot, Hamm’s Bear, that was a staple for Theodore Hamm’s Brewing Company for years. “He was breaking barriers when he was in commercial art,” Robert DesJarlait said about his dad. “When other Ojibwe people in Minnesota found out (about his success) as a Ojibwe artist, they were proud of that, too.” An autobiography by Patrick DesJarlait, along with author Neva Williams, was published in 1994. The book is about DesJarlait’s life growing up in Red Lake, his military career and his life as an artist. When he was a young boy, Branchaud said her dad went blind for about a year and traditional medicines by his mom slowly helped DesJarlait regain his vision. Learning that history about her dad and her grandmother, Branchaud went into a career in healthcare. In the Navy, DesJarlait’s art talent was utilized. First as an instructor in Arizona at the Poston Internment Camp for Japanese internees and later at the U.S. Naval Academy in San Diego where he created animated training films. Prints of DesJarlait’s art work are still available online via a website Branchaud helps manage. Branchaud, 65, remembers growing up and seeing her dad working on his craft at the table in their suburban Minneapolis home. “He was at the kitchen table, doing his tracing, then watercolors came out and voilà a beautiful painting in front of him,” Branchaud said. “Those are the kind of memories I have.” Over the April 18 weekend, Branchaud went grocery shopping and hit the dairy section and purposely looked for Land O’Lakes items. She found an unsalted whipped butter tub that still has Mia. She didn’t have much luck finding any signature items with the image. “No real butter, no butter, butter,” she said with a laugh. Dalton Walker, Red Lake Anishinaabe, is a national correspondent at Indian Country Today. Follow him on Twitter - @daltonwalker Note: Originally published at Anishinaabe Perspectives on 2/28/2019 A few weeks ago, I was looking at my father’s art for an art project I’m working on and I was referencing the floral motifs he used in his work that focused on dancers. One particular work that caught my attention was War Dancers from 1964. I think when you look at his oeuvre of powwow dancers - War Dancers, The Chippewa Dancers (1968), The Chippewa Hoop Dancer (1968), Chippewa Dancer (1964) – the observer has a tendency to see the overall images and miss some of the finer detail in the regalia that the dancers are wearing. One is aware of the floral motifs but the eye wanders over them and doesn’t really connect with the detail. It’s understandable since an observer is taken in by the rich array of colors of his work. Indeed, the color arrangements are unlike men’s dance regalia from the 1960s. What the observer sees is a rich palette of colors that forms the aesthetic of a modern Native American artist. And the results are colors that form and shape the regalia in brilliant hues. In retrospect, his colors are something of a paradox, at least a paradox at the time the dancers were painted. Consider War Dancers. In this work, we see eagle feather bustles that are pink, green, and yellow-gold; green and yellow-gold eagle fans; and yellow, pink, and blue anklets which, at that time, were commonly white or red. Even in the roaches that, in the 60s, were red, we see an array of colors – reddish-brown, blue, brownish-gold. And then there are the floral motifs. One might assume that he simply painted the floral designs that he saw at powwows, and that he used books that featured floral designs. However, he couldn’t really access books since books with floral designs weren’t available in the 60s. So, he had to rely on what he observed at powwows. Obviously, he had a sharp memory given the floral motifs in his work. However, he was making his own floral designs based on the images that were stored in his memory. He was like a bandolier bag maker from the late 1800s and used paint instead of beads to make his arrangements. He had to adapt floral forms to paint in the same way that bandolier beaders adapted beads from the traditional form of quills. In this way, he wasn’t simply copying floral designs – he was creating his own floral forms. One particular floral motif that caught my eye in War Dancers is a leaf divided into four colors that are separated by the vein in the leaf. It reminded me of a bandolier bag that features red and blue leaves. Those red and blue leaves have always mystified me. They are such a departure from bandolier color aesthetics. How and why did the bandolier bag artist make such a departure? We know leaves aren’t a deep, solid red or blue. But this particular artist decided that they can be red or blue. Those red and blue leaves go beyond the norm of color used then and represent a step into modernism – at a time when modernism was unknown to Ojibwe bandolier artists. In that sense, modernism is the next logical step in art. This particular bandolier artist was expressing modernism in terms of color. Most interestingly, those leaves strongly connect to Fauvism although, as noted, such art was unknown to Ojibwe artists. My father’s four-colored leaf offers yet another parallel in terms of color aesthetics. In his palette, we see an array of leaf colors – blue, red, gold. But the four-colored leaf is a departure. In this particular leaf, we see four colors – light blue, light green, yellow, and pink – divided by the vein. A variation of the leaf on a dancers’ armband rearranges the colors to green, yellow, light blue, and red. There are also leaf variations on the dance aprons including one with green, white, blue, and yellow. Unlike the bandolier artist who didn’t have exposure to modern art, my father did. He was familiar with Mexican muralism, Cubism, and Fauvism. And he is, of course, considered the first Native American modernist artist. Yet, the four-colored leaf represents something different. Like the red and blue bandolier leaves, the four-colored leaf also intrigues me. It seems like a logical step for him to take, but what a step it was to go beyond the norm and create something new. In hindsight, I like to think that my father was something of a visionary in regard to regalia color. At a time when these colors were virtually unknown in regalia, they have become common today. I’m not suggesting that he had any influence on today’s colors. In the powwow world, the vast array of brilliant, beautiful colors was the next logical step into the modern powwow. The four-colored leaf, painted fifty-five years ago, was a vision of what was to come. Detail - Armband, "War Dancers," ca. 1964 Detail - Dance Apron, "War Dancers," ca. 1964 © 2019, Robert DesJarlait

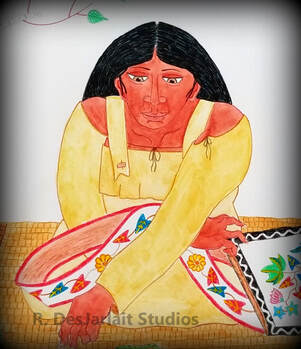

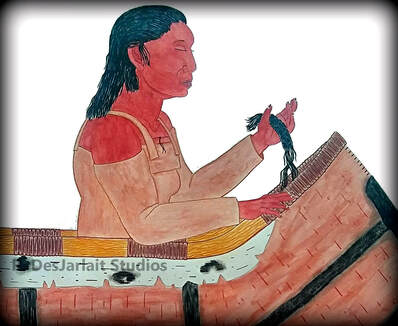

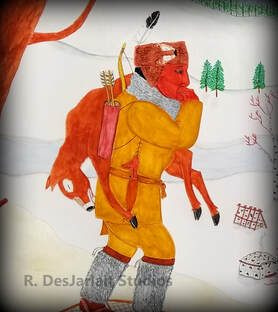

“One day, the Earth was submerged by a destructive flood sent by Mishibijiw, the Great Underwater Serpent. Nenabozho, our Great Uncle, survived. Drifting on a log, he obtained pebbles of dirt from the muskrat. After planting the dirt on his log, the Earth regrew and new life reemerged from the life that existed before.” In April 2013, I heard the three words that you don’t want to hear – you have cancer. I thought my life was over. I was 66 years old, retired, and at that point in my life, art was far from my mind. One day, I took a walk in the halls of the cancer ward with my IV stand rolling beside me. My prognosis was good. Following surgery for the removal of my ascending colon, my cancer was classified as Stage I meaning the cancer hadn’t metastasized and chemo wasn’t required. As I walked along the hallways of the cancer ward, I saw walls covered in art. I had no idea who the artists were. I asked a nurse: “Who are the artists?” She replied that some of them were by former cancer patients and others were from families who had lost a loved one to the disease. And, therein, a seed was sown and a promise made that someday I would return with a painting to join the walls of art in the cancer ward. But any aspirations of returning to art came to a jolting halt in May 2016. My annual CT scan revealed a lesion on the left lobe of my liver. This time around, my surgery was preceded by four rounds of neoadjuvant chemo and followed by twelve rounds of adjuvant chemo. As a result of my recurrence, I became a Stage IV cancer survivor. In November 2018, Reemergence became a part of my cancer journey. Cancer survivors live a cautiously optimistic life. We really can’t look too far into the future. Goals and priorities need to be in the short term. The ideas that floated through my mind in the cancer ward came to fruition. But it was really a question of whether I could return, or more specifically reemerge, to the fine art form I established in the 1980s. “Gidagaabinesh” (Spotted Bird) was the first work and a tribute to Herb Sam, one of my spiritual mentors and advisors who passed from liver cancer in September 2018. I didn’t have watercolors or brushes, so I decided to use colored pencils and, for the first time, watercolor pencils. I decided to do the work encompassed in a circle – the circle was a hallmark of my illustration art in the 1990s and early 2000s. “Gidagaabinesh” was a test of sorts. Did I retain my skills as a fine artist after a nearly 35 year absence? Or had my abilities diminished? With the finished work, I found that my palette hadn’t lessened and my aesthetics had matured. Indeed, rather than being diminished, they had improved. It was almost as if they had been in limbo and waited for the reopening of the channels to my creativity. I did a sister piece - “Aazha miinawaa Manidoo-Giizhikens” (Aazha and the Spirit Tree) with two main characters from a children’s book I’m writing about two Ojibwe children with childhood cancers. Manidoo-Giizhikens (the Spirit Tree) has a special place in my heart following a photo shoot there in 2016 with well-known photographer Ivy Vainio. After completing the two works, I decided to create a body of work called Reemergence. From late November to late January, I worked on a number of pencil studies that would form the series. The art largely reflected the themes I developed in the 1980s – scenes of the traditional, everyday roles of Ojibwe-Anishinaabe women and men in the 1700s-1800s. In mid-March, I obtained watercolors, gouache (a new medium for me), and brushes, and began working on the paintings. By mid-June, I completed 15 paintings for a total of 17 works for the Reemergence series. The title reflects my reemergence as a fine artist. But it also reflects my reemergence after battling cancer for seven years. Reemergence is not cancer art per se; rather, it’s art by a cancer survivor who is Ojibwe-Anishinaabe who is an artist. The art is a paradigm of creativity and healing in a time of sickness. However, Reemergence has a deeper meaning. In a cultural context, Nenabozho’s story has a metaphorical meaning in relation to my cancer experience. Cancer and Mishibijiw are interrelated as malevolent beings that bring death, chaos, and destruction. The log is my physical body and Nenabozho represents my spirit. The pebbles of dirt are the medicines that help heal me. And, forthwith, a new life reemerges from the life that existed before. Our elders teach that our personal lives move in a circle. We always come back to a point that we’ve left behind. We may bypass the point and move on. Or we may stop at the point and find something that provides a deeper meaning and direction on our path. With Reemergence, I’ve reached such a point. Gidagaabinesh (Spotted Bird) Watercolor Pencil / Colored Pencil Herb Sam was one of my spiritual mentors and advisor. He passed from liver cancer in September 2018. His Ojibwe name was Gidagaabinesh (Spotted Bird). He stands on the shore of Misi-zaaga'igan (Grand Lake, i.e., Lake Mille Lacs) offering asemaa (tobacco) to a spotted bird/golden eagle. The eagle carries a purple ribbon – purple is the color for all cancers. In the background is Spirit Island, a prominent feature in the lake. Aazha miinawaa Manidoo-Giizhikens (Aazha and the Spirit Tree) Watercolor Pencil / Colored Pencil Aazha is a character in my book, “The Luminaria” (unfinished), a Young Teen novel (ages 12-15) about two Ojibwe children with childhood cancers. She is offering asemaa and Jesse (the protagonist) holds an eagle feather. They are standing under Manidoo-Giizhikens (the Spirit Tree) on the shores of Anishinaabewi-gichigami (the Great Sea of the Anishinaabeg,i.e., Lake Superior). Manidoo-Giizhikens is located on the Gichi Onigamiing (Grand Portage) reservation. This sacred cedar tree grows on rocks of granite. I was part of a photo shoot with photographer Ivy Vainio in 2016. Touching the tree has left an indelible memory in my mind. Ma’iingan Ogichidaa (Wolf Warrior) Watercolor / Watercolor Pencil / Colored Pencil In our origin story, Original Man and Ma’iingan (Wolf) were chosen by Gichi-Manidoo (the Creator) to roam the Earth and give names to all of Creation. Upon completing their task, Gichi-Manidoo separated them but said that whatever fate befell one would befall the other. And it came to pass that like Ma’iingan, the Anishinaabeg were hunted for their hair, their hunting grounds diminished and stolen, and they were branded as merciless savages. Today, our fates remain intertwined. Giigoonyikekwewag (The Fisherwomen) Watercolor / Watercolor Pencil Although there were specific gender roles for Ojibwe women and men, roles overlapped and were shared by both. Setting and collecting asabiig (nets) is often regarded as a male activity. However, women also participated in bagidawaa (net fishing). In the painting, two ogaawag (walleye), ginoozhe (Northern pike), and adikomeg (whitefish) have been caught in the asab (net). The women (as all the women in the series) are wearing strap dresses woven from mazaanaatigoog (nettles). Doodoo miinawaa Abinoojiinh (Mother and Child) Watercolor / Colored Pencil Doodoo is an older term used for mother. It is derived from doodooshim (breast) and doodooshaaboo (milk); usually preceded with a personal prefix – Indoodoo (my mother), Gidoodoo (your mother). One of the things I wanted to do was to use floral and leaf motifs from Ojibwe bandolier beaded art. The hairpiece and bracelet are specifically from beaded art; the earring is birch bark with a hummingbird made from quills. The mother is reclining on her side with the baby in her arms. Abagwe’ashk Akwe (Cattail Woman) Watercolor / Gouache Abagwe`ashkoon (Cattails) served a variety of services including medicine and food. Abagwe’ashk fluff was used as insulation in winter wiigiwaman (birch bark lodges). It was also used to line a baby’s loincloth to serve as a type of disposable diaper. When the fluff was soiled, it was disposed of and fresh fluff added. In this piece, a young, pregnant mother-to-be is collecting fluff for her baby. Gashkibidaagan Akwe (Bandolier Bag Woman) Watercolor / Gouache Gashkibidaaganag (Bandolier bags) was a high art form that developed among the Ojibwe in the late 1800s. It was primarily a woman’s art. Gashkibidaaganag were part of maziniminensikaan (beadwork) that featured an array of floral and leaf motifs composed with seed and glass beads. Traditionally, dyed quills and moose hair were used. The introduction of manidoominag (beads) via European traders led to newer art forms that expressed Woodland identity. Maziniminensikaan was arranged on leggings, men’s aprons, strap dress panels, moccasins, and shirts. Compositionally, designs were usually arranged symmetrically. Gashkibidaaganag were the apex of beading art. The palette of Gashkibidaaganag artists often was reminiscent of fauvism palettes with bold, vibrant colors that weren’t representational of the floral and leaf forms that they depicted. Dakobijigan (Tied Rice) Watercolor / Gouache Before the harvest, women would go out and tie the manoomin (wild rice). They used strips of wiigibiish (basswood) that was rolled into a ball. A panel was worn on their back with birch bark ringlets through which the wiigibish was threaded to keep the wiigibish from tangling. They used a hooped pole to pull the manoominaatigoon (wild rice stalks) down to be tied. The wiigibish was dyed and allowed for a family’s harvesting area to be marked. (This method is still used by many families today.) The zhiishiib (duck) flying overhead has balls of mud stuck to its webbed feet. The mud balls are embedded with manoomin seeds. The mud balls dropped off the feet of the zhiishiib, sunk to the bottoms of the waters to the sediment below and, thereby, spread and planted the seeds for future growth. Manidookewin (Ceremony) Watercolor / Gouache / Watercolor Pencil The ceremony isn’t about the sacred objects that are next to the mother. Although they play a role, the ceremony is about the love between the mother and her child and the resultant bonding between the two. As in any ceremony, the bonding is reciprocal. The love projected by the mother is returned by the child. The painting is semi-autobiographical in a metaphorical way – the mother is my mother and I am the child. The unconditional love continues to this day, long after she has passed to the Spirit World. Aadizookaan Makizin-Ataagewin (Origin of the Moccasin Game) Watercolor / Gouache The moccasin game is played among many tribes and there are origin stories associated with its creation. Among the Ojibwe, the game came through a dream-vision. One night, a sickly young boy dreamed he was walking through the woods. He came upon a friendly Makwa (Bear). Makwa spoke to him and asked him to sit down. Makwa said: “I know you are sick. I will teach you a game to help heal you and give you a long life.” Before him, Makwa had a reed mat spread out. There were sticks to help keep count of wins. There were four bear paws and four pebbles of various sizes. Makwa said: “I will hide these pebbles under the paws. To win, you must correctly guess under which paw the largest pebble lies. Use this long stick to flip over the paw where you think the pebble is.” Makwa then picked up the pebbles and hid them in his paws. He waved his arms around and stopped four times. With each stop, he deftly slid a pebble under a paw. As the boy played, Makwa sang moccasin game songs on his hand drum. When they finished the game, Makwa said: “Take this game back to your village. Teach the men how to play it. Use moccasins instead of bear paws. The game will give men the opportunity be together and socialize. And, it will give them good health.” This is how Makizin-Ataagewin originated among the Ojibwe. Binawiigo (In the Beginning) Watercolor / Gouache This painting is essentially a self-portrait that connects me to the traditional art form of mazinibii`iganan (pictographs). Mazinibii`iganan can be found all across Anishinaabeg-Aki (the Land of the Anishinaabe). Mazinibii’iganan were mages were painted on rocks. Another method was mazinaabikiniganan (petroglyphs) - images that were etched on rocks. Images were more commonly painted than etched. Onaman, a red paint, was used. Binding agents were fish guts or bear fat. Onaman was considered to be sacred. In the origin story, the Thunderbird and Great Beaver engage in a battle. The Thunderbird flies a lot and carries the Great Beaver into the skies. The talons of the Thunderbird pierce the Great Beaver and its blood rains down upon the Earth. The blood sinks into the sand. The red sand is onaman and was used to paint mazinibii`iganan images on rocks. The array of images included spirit-beings, mythological animals, and humans composed into narratives about visions, dreams, stories, migrations, hunting and warrior parties. However, interpretations of the compositions are difficult to decipher. In “Binawiigo,” I chose two pictographs found on a lake in Ontario. The exact meaning of these two images – a human form and a wolf – is unknown. But it reminds me of the origin story about Original Man and Ma’iingan (Wolf). However, the human form also reminds me of Nenabozho. Nenabozho was a shape shifter and often transformed himself into a waabooz (rabbit). The long ears on the human figure seems to indicate that it is Nenabozho who has partially transformed. Misko Magoodaas (Red Dress) Watercolor / Gouache We usually associate MMIW (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women) with events happening today. But, it didn’t begin on dark, desolate highways. MMIW has existed ever since the Invasion and the colonization of our homelands. The fur trade wasn’t just about economic motives for tribes. It was also about the servitude of Native women as “country wives.” And, women forced into prostitution at forts and trading posts. Rape, beatings, and murder became the fate of many of these women. “Misko Magoodas” is about one of those victims – a woman who has been raped. She has cut off her braids as a sign of her grief. Her mirrored reflection in a red strap dress signifies her journey into the cauldron of historical trauma. Niibinishi Gabeshi (Summer Camp) Watercolor / Gouache The Ojibwe were a semi-nomadic people who followed seasonal rounds to areas of subsistence. The two main camps were the niibin (summer) camps and biboon (winter) camps. Daagwaagin (Fall) and ziigwan (spring) camps were more short-term and limited to gathering manoomin (wild rice) in the fall and ziinzibaakwad (maple sugar) in the spring, and late spring and early fall was a time for ceremonies. Niibinishi Gabeshi (Summer Camp) included a variety of activities – gathering birch bark, gathering plants for food and medicine, hunting and trapping, netting fish, growing food, and tanning hides for winter. The summer wiigiwam usually differed from the winter lodge in that reed mats were used for the walls. The wiigiwam provided protection from the elements yet was ventilated and cool on hot summer nights. Basswood twine was used to secure the roof and walls to frames made from ash saplings. Logs on the sides further secured to roof to the frame. Small A-frame structures were built to store various implements. Pits were dug, lined with birch bark with birch covers to keep foodstuffs cool and out of reach of animals. Rock mortars and pestles were used to grind mandaamin (corn). Small garden plots were common and planted with agasimaan (squash), mashkodesiminag (beans), and mandaamin (corn). Historians of colonization portray tribal life as drab and tedious. However, tribal peoples didn’t, like the colonizers, dominate nature; rather, they were dominated by nature. They lived a wholesome existence that was in balance with the Original Instructions mandated by Gichi-Manidoo (the Creator). Maamiikwendamaw Nagawbo (Remembrance – Boy in the Woods / Patrick Robert DesJarlait) Watercolor / Gouache My father’s Ojibwe name was Nagawbo because he was always in the woods and observing the things around him. He was also given another name – Gwiwizens Odayn Ozhibii ignaak (Boy with a Pencil). He is often attributed as the first Native American modernist in fine arts. But his artistic abilities weren’t limited to fine art. He was also a commercial artist who worked for ad agencies in Minneapolis in the 1950s and early 60s. His most famous creation was the Hamm’s Beer Bear. As a tribute to my father, I’ve painted the bear in his favorite pose – dancing on a log. But rather than a pine log, I have him dancing on a birch log to emphasize his connection to the Ojibwe. And, I’ve given him an update with an otter turban and bandolier bag. The ogaa (walleye) never appeared in the cartoons. So, I’ve added an ogaa to emphasize my father’s connection to Red Lake where our ogaawag are the filet mignon of the Ginoozhe-Aki (the Fish World). Wiizhaandige Gitigaan (Unfinished Garden) Watercolor / Gouache “I want us to be doing things, prolonging life's duties as much as we can. I want death to find me planting my cabbages, neither worrying about it nor the unfinished gardening.” ~ Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) Quotes, sayings, and phrases provide inspiration for cancer survivors. They become embedded in one’s thoughts and perspectives. For me, Montaigne’s narrative about unfinished gardening strikes a deep chord. It speaks to me about continuing life’s journey and attaining goals within our grasp. My death will find my garden unfinished, but that matters not. What I’ve accomplished is what is important. “Unfinished Garden” then is about my cancer journey. Several of the floral and leaf motifs have a personal meaning. A manidoog floats near me, a shape with translucent wings and a red bead representing the spirit being. The unfinished garden is symbolized by the large leaf that is near the center. Half of the leaf is finished, half is unfinished. Life’s end becomes an unfinished garden. Giiwosewinini (The Hunter) Watercolor / Gouache Biboon was a time for hunting waawaashkeshiwag (deer), moozoog (moose), and adikwag (caribou), and for trapping fur bearing animals. For women, indoor activities included making food utensils and birch bark food containers, and making clothing and moccasins that were often intricately decorated with dyed porcupine quills. Biboon was also a time for learning. Origin and Nenabozho stories were told to teach children their history, spiritual beliefs, creation of the natural world, and cosmology of the Anishinaabeg people. Many camps were located near rivers to allow access for ice fishing. The outside walls of the wiigiwanan (lodges) were covered with birch bark sheets that provided protection from the cold winds of winter. Abagwe`ashk (Catttail) fluff or moss was placed between the inner walls of reed mats and outer birch walls to provide insulation. “Giiwosewinini” depicts a hunter returning with a small waawaashkeshi (deer) that will help feed his village. The gijigaaneshiinzhi (black-capped chickadee) is the bird of winter who is able to survive sub-zero temperatures. He represents the spirit of the Anishinaabeg who, like the bird, are able to survive the harsh conditions of Biboon. Mitigwaakokwi Inoodewiziwin (Woodland Family) Watercolor / Gouache The family in this painting represents the contemporary generation of the ancestors who are depicted in the paintings of traditional life. They are the people of the Seventh Fire. In our Seven Fires Prophecies it is said: “In the time of the Seventh Fire New People will emerge. They will retrace their steps to find what was left by the trail. Their steps will take them to the Elders who they will ask to guide them on their journey.” They are the New People who have survived genocide, linguicide, ecocide of their homelands, forced assimilation, institutionalized racism, historical trauma, and intergenerational trauma. They are retracing their steps back to their language, cultural practices and beliefs, and traditional activities that define Ojibwe identity. It is a long path back but they are finding what was left by the trail. © 2019, Robert DesJarlait

|

AuthorRobert DesJarlait Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed