|

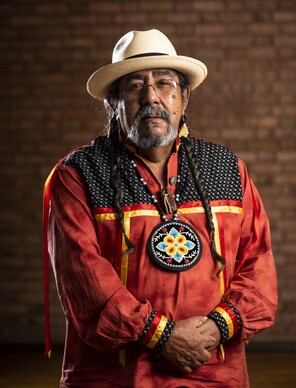

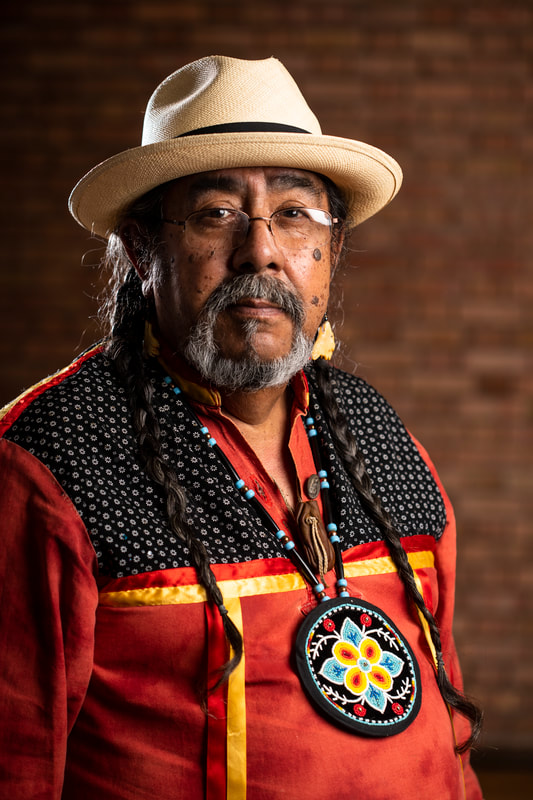

By A.R.V. van Rheenen Robert DesJarlait is a member of the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation and a fine artist Photo by Tj Turner Local artist recognized by ECRAC for excellence Endaso-Giizhik, Robert DesJarlait, is part of the bear clan. DesJarlait describes the bear clan within his Ojibwe culture as the “warrior clan.” “We help guard and protect the community,” he shared in a recent phone interview. And while clans ebbed after colonization and reservations were implemented by outside forces, DesJarlait said many people still relate to their clan and identify with their characteristics. He is one of those people. As an artist, DesJarlait, a member of the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation, sees his heritage of the bear clan reflected in his work. “I’m protecting my community through my art, because I’m educating through my art,” he said. He grew up immersed in art. His father, Patrick DesJarlait, was a successful artist in his own right, and one of the first Native American modernist artists, DesJarlait said. He was born on the Red Lake Reservation, but early in life, his family moved to the Twin Cities area so his father could pursue more opportunities. Patrick went on to create the famous Hamm’s beer bear, as well as the Land O’Lakes maiden. “My dad was basically my art teacher,” DesJarlait shared. While DesJarlait didn’t paint early on, he said he loved to draw and had access to his father’s art studio. It was a “good experience” to have his dad as his art teacher, he added. But DesJarlait decided not to go to art school after high school graduation, like people expected him to. During the 70s, he shared, he got caught up in drinking and drugs. In 1982, he gave it up. And then two years later, at age 36, he got back into art. He knew he could be a writer or an artist, and he chose the brush over the pen to become a gallery artist. His first show was at Avanyu Gallery in Minneapolis. While his father painted scenes of Ojibwe life in the 20s, 30s and 40s, life as he knew and saw it, DesJarlait decided to “go back further,” to the pre-Reservation period and early Res period, working primarily in watercolor and then in acrylic. As his work became known, DesJarlait said, “I began lecturing about my culture through my art.” He developed illustrations for various Native American curricula, began doing murals and community art projects – all those things “took away” from his painting, he said. In 2013, he received a colon cancer diagnosis. Thankfully, it was caught in stage one, and he was able to get the cancerous part removed. But in 2016, a tumor on his liver was found, which required surgery and several rounds of chemo, in addition to surveillance with more regular scans. It was after that struggle with his health that DesJarlait focused in on painting once more. He staged a gallery show in Minneapolis and called it “Reemergence.” It was a reemergence in life, in art, a step into all that the future held for him after twice-surviving cancer. After Reemergence, he set up a gallery show in Duluth, right as the pandemic set in. About 10 years ago, DesJarlait moved with his family to the Mille Lacs area; he now resides in Onamia. While living in the cities, he said, he wasn’t eligible for various grants. But living in this region afforded him the opportunity to apply for a mid-career grant through the East Central Regional Arts Council. The last two years, he’s won an award in their annual IMAGE Art Show; in 2021, he won the merit award. This year, he won an excellence award. “I really appreciate the recognition.” Out of 129 participating artists, “I didn’t know how I would do.” ECRAC, which is based out of Hinckley, will host an art show put on by DesJarlait in their gallery in February 2023. The piece he submitted this year, Ojibwe Mitigwaki Niimid (Ojibwe Woodland Dancers), was displayed in the gallery during November with the other award-winners. Ojibwe Mitigwaki Niimid / Photo by Robert DesJarlait The judges for this year’s IMAGE show were artist Jonathan Thunder of Duluth and art administrator Bethany Whitehead of St. Paul. Mary Minnick-Daniels, executive director of ECRAC, said in an email that the judges “give their awards on the artistic merit of the artwork based on the medium used.” In DesJarlait’s watercolor piece, they saw the “techniques used and the expertise exhibited.” She added, “The judges noted how his artwork showed great movement and that it also conveys a true emotional impact.” DesJarlait is a dancer himself. “We’ve been a powwow family,” he shared. His wife makes outfits for the family, and “we’re on the powwow trail all summer long.” He has long participated in the men’s traditional dance; a few years ago, a new dance was introduced. The dance has actually been around a long time, and an outfit he and his wife had worked on together was the right fit for the war dance, one that has been big in the Great Lakes area. DesJarlait called it “unique” and “energetic, … the young guys are phenomenal,” and it’s one women play a role in as well. Influenced by his father’s work, who did a number of paintings about dancers, DesJarlait started to conceptualize his piece about the woodland dancers. After studying one of his father’s paintings depicting Chippewa dancers, he came up with a composition he liked. DesJarlait’s painting displays colorful eagle feathers and bandolier bags. Like his father before him, DesJarlait decided to depict the feathers with blue, pink and cream colors; that was something they didn’t have in the 70s at the dances, DesJarlait said, “but that’s how he portrayed it.” Now, it’s “not uncommon to find dyed feathers.” The bandolier bags DesJarlait painted depicted “geometric images,” rather than floral work. In details like that, DesJarlait “tried to capture what that dance is about.” DesJarlait always names his artwork in the Ojibwe language, of which he is a learner. “It’s important to me as an individual,” he said. “Language shapes your mindset,” and the Ojibwe language goes back hundreds of years. It’s a language that’s descriptive and full of movement – he said he believes about 80-85% of it is made up of verbs. The Ojibwe people, historically, “were basically an oral people,” DesJarlait said. “Our people learn through storytelling.” He depicts this in his art, one being in Giizhig Ikwe miinawaa Gichi-Mikinaak (Sky Woman and the Great Turtle); that piece was commissioned by the University of Minnesota Morris, but DesJarlait had “artist’s choice” for what to paint. Stories such as the one shown in this painting provide education for young people and adults, too, DesJarlait said. Giizhig Ikwe miinawaa Gichi-Mikinaak / Photo by Tj Turner For the works of art themselves, DesJarlait said the length of time it takes to complete them “depends on how much time I want to put into it.” Generally he sticks to a schedule. While a younger artist, he could paint all night if he wanted. Now, he has a day schedule, starting out with his coffee and breakfast and then painting all day until about 6 p.m. His Sky Woman piece took about two months, although an injury that kept him from being on his feet and working actually stretched it to about three-and-a-half months. He’s back to using watercolor, specifically what is called gouache. Gouache is more opaque, DesJarlait said, and with it, an artist has “more freedom to go over mistakes you might make.” He continues to explore Ojibwe origin stories, but he also includes more contemporary renderings as well. DesJarlait’s Ojibwe name, Endaso-Giizhik, means “everyday,” he said. It was a name he received “late in life,” by a spiritual man of Mille Lacs, Herb Sam. At first, DesJarlait admitted, he didn’t understand how the simple name captured what it means to be part of the bear clan. But he grew to understand how the warriors secured their villages, an act that occurred everyday. Sam told DesJarlait about another Ojibwe man who had that name, an “old man who was always taking his kids to the powwow”; Sam said he saw that in DesJarlait. That, too, flows into being part of the bear clan. “I feel my art educates people,” DesJarlait said. And this education is protection of his people. To see more of DesJarlait’s art and learn more about his extensive work, you can visit his website at www.robertdesjarlaitfinearts.com/ Article reprinted from the Mille Lacs Messenger 11/30/2022 online issue.

© Mille Lacs Messenger, 2022

0 Comments

Ojibwe Mitigwaki Niimid, 24 x 33, Watercolor (Opaque) "Ojibwe Mitigwaki Niimid" (Ojibwe Woodland Dancers) was awarded an Artistic Excellence Award at the East Central Regional Arts Council 2022 IMAGE Art Show. It was one of ten Excellence Awards given out of a field of 130 visual artists. The judges for this year's IMAGE art were artist Jonathan Thunder of Duluth and art administrator Bethany Whitehead of St. Paul. Mary Minnick-Daniels, ECRAC, said...that the judges "give their awards on the artistic merit of the artwork based on the medium used." In DesJarlait's watercolor piece, they saw the "techniques used and the expertise exhibited." She added, "The judges noted how his artwork showed great movement and that it also conveys a true emotional impact." (Mille Lacs Messenger) |

AuthorRobert DesJarlait Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed