|

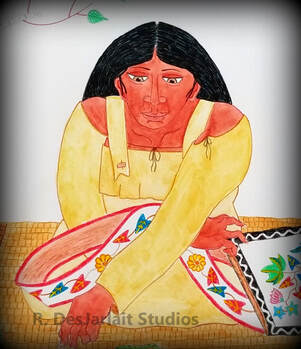

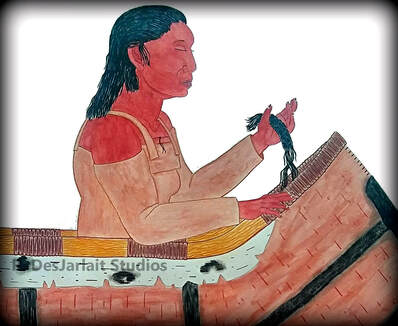

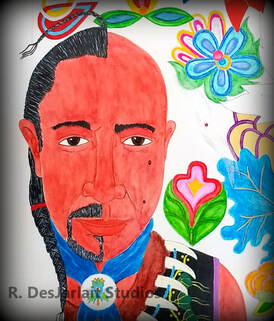

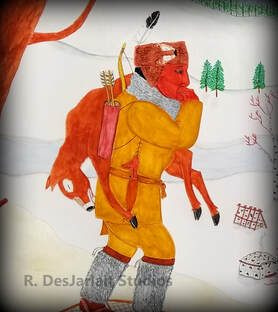

Gidagaabinesh (Spotted Bird) Watercolor Pencil / Colored Pencil Herb Sam was one of my spiritual mentors and advisor. He passed from liver cancer in September 2018. His Ojibwe name was Gidagaabinesh (Spotted Bird). He stands on the shore of Misi-zaaga'igan (Grand Lake, i.e., Lake Mille Lacs) offering asemaa (tobacco) to a spotted bird/golden eagle. The eagle carries a purple ribbon – purple is the color for all cancers. In the background is Spirit Island, a prominent feature in the lake. Aazha miinawaa Manidoo-Giizhikens (Aazha and the Spirit Tree) Watercolor Pencil / Colored Pencil Aazha is a character in my book, “The Luminaria” (unfinished), a Young Teen novel (ages 12-15) about two Ojibwe children with childhood cancers. She is offering asemaa and Jesse (the protagonist) holds an eagle feather. They are standing under Manidoo-Giizhikens (the Spirit Tree) on the shores of Anishinaabewi-gichigami (the Great Sea of the Anishinaabeg,i.e., Lake Superior). Manidoo-Giizhikens is located on the Gichi Onigamiing (Grand Portage) reservation. This sacred cedar tree grows on rocks of granite. I was part of a photo shoot with photographer Ivy Vainio in 2016. Touching the tree has left an indelible memory in my mind. Ma’iingan Ogichidaa (Wolf Warrior) Watercolor / Watercolor Pencil / Colored Pencil In our origin story, Original Man and Ma’iingan (Wolf) were chosen by Gichi-Manidoo (the Creator) to roam the Earth and give names to all of Creation. Upon completing their task, Gichi-Manidoo separated them but said that whatever fate befell one would befall the other. And it came to pass that like Ma’iingan, the Anishinaabeg were hunted for their hair, their hunting grounds diminished and stolen, and they were branded as merciless savages. Today, our fates remain intertwined. Giigoonyikekwewag (The Fisherwomen) Watercolor / Watercolor Pencil Although there were specific gender roles for Ojibwe women and men, roles overlapped and were shared by both. Setting and collecting asabiig (nets) is often regarded as a male activity. However, women also participated in bagidawaa (net fishing). In the painting, two ogaawag (walleye), ginoozhe (Northern pike), and adikomeg (whitefish) have been caught in the asab (net). The women (as all the women in the series) are wearing strap dresses woven from mazaanaatigoog (nettles). Doodoo miinawaa Abinoojiinh (Mother and Child) Watercolor / Colored Pencil Doodoo is an older term used for mother. It is derived from doodooshim (breast) and doodooshaaboo (milk); usually preceded with a personal prefix – Indoodoo (my mother), Gidoodoo (your mother). One of the things I wanted to do was to use floral and leaf motifs from Ojibwe bandolier beaded art. The hairpiece and bracelet are specifically from beaded art; the earring is birch bark with a hummingbird made from quills. The mother is reclining on her side with the baby in her arms. Abagwe’ashk Akwe (Cattail Woman) Watercolor / Gouache Abagwe`ashkoon (Cattails) served a variety of services including medicine and food. Abagwe’ashk fluff was used as insulation in winter wiigiwaman (birch bark lodges). It was also used to line a baby’s loincloth to serve as a type of disposable diaper. When the fluff was soiled, it was disposed of and fresh fluff added. In this piece, a young, pregnant mother-to-be is collecting fluff for her baby. Gashkibidaagan Akwe (Bandolier Bag Woman) Watercolor / Gouache Gashkibidaaganag (Bandolier bags) was a high art form that developed among the Ojibwe in the late 1800s. It was primarily a woman’s art. Gashkibidaaganag were part of maziniminensikaan (beadwork) that featured an array of floral and leaf motifs composed with seed and glass beads. Traditionally, dyed quills and moose hair were used. The introduction of manidoominag (beads) via European traders led to newer art forms that expressed Woodland identity. Maziniminensikaan was arranged on leggings, men’s aprons, strap dress panels, moccasins, and shirts. Compositionally, designs were usually arranged symmetrically. Gashkibidaaganag were the apex of beading art. The palette of Gashkibidaaganag artists often was reminiscent of fauvism palettes with bold, vibrant colors that weren’t representational of the floral and leaf forms that they depicted. Dakobijigan (Tied Rice) Watercolor / Gouache Before the harvest, women would go out and tie the manoomin (wild rice). They used strips of wiigibiish (basswood) that was rolled into a ball. A panel was worn on their back with birch bark ringlets through which the wiigibish was threaded to keep the wiigibish from tangling. They used a hooped pole to pull the manoominaatigoon (wild rice stalks) down to be tied. The wiigibish was dyed and allowed for a family’s harvesting area to be marked. (This method is still used by many families today.) The zhiishiib (duck) flying overhead has balls of mud stuck to its webbed feet. The mud balls are embedded with manoomin seeds. The mud balls dropped off the feet of the zhiishiib, sunk to the bottoms of the waters to the sediment below and, thereby, spread and planted the seeds for future growth. Manidookewin (Ceremony) Watercolor / Gouache / Watercolor Pencil The ceremony isn’t about the sacred objects that are next to the mother. Although they play a role, the ceremony is about the love between the mother and her child and the resultant bonding between the two. As in any ceremony, the bonding is reciprocal. The love projected by the mother is returned by the child. The painting is semi-autobiographical in a metaphorical way – the mother is my mother and I am the child. The unconditional love continues to this day, long after she has passed to the Spirit World. Aadizookaan Makizin-Ataagewin (Origin of the Moccasin Game) Watercolor / Gouache The moccasin game is played among many tribes and there are origin stories associated with its creation. Among the Ojibwe, the game came through a dream-vision. One night, a sickly young boy dreamed he was walking through the woods. He came upon a friendly Makwa (Bear). Makwa spoke to him and asked him to sit down. Makwa said: “I know you are sick. I will teach you a game to help heal you and give you a long life.” Before him, Makwa had a reed mat spread out. There were sticks to help keep count of wins. There were four bear paws and four pebbles of various sizes. Makwa said: “I will hide these pebbles under the paws. To win, you must correctly guess under which paw the largest pebble lies. Use this long stick to flip over the paw where you think the pebble is.” Makwa then picked up the pebbles and hid them in his paws. He waved his arms around and stopped four times. With each stop, he deftly slid a pebble under a paw. As the boy played, Makwa sang moccasin game songs on his hand drum. When they finished the game, Makwa said: “Take this game back to your village. Teach the men how to play it. Use moccasins instead of bear paws. The game will give men the opportunity be together and socialize. And, it will give them good health.” This is how Makizin-Ataagewin originated among the Ojibwe. Binawiigo (In the Beginning) Watercolor / Gouache This painting is essentially a self-portrait that connects me to the traditional art form of mazinibii`iganan (pictographs). Mazinibii`iganan can be found all across Anishinaabeg-Aki (the Land of the Anishinaabe). Mazinibii’iganan were mages were painted on rocks. Another method was mazinaabikiniganan (petroglyphs) - images that were etched on rocks. Images were more commonly painted than etched. Onaman, a red paint, was used. Binding agents were fish guts or bear fat. Onaman was considered to be sacred. In the origin story, the Thunderbird and Great Beaver engage in a battle. The Thunderbird flies a lot and carries the Great Beaver into the skies. The talons of the Thunderbird pierce the Great Beaver and its blood rains down upon the Earth. The blood sinks into the sand. The red sand is onaman and was used to paint mazinibii`iganan images on rocks. The array of images included spirit-beings, mythological animals, and humans composed into narratives about visions, dreams, stories, migrations, hunting and warrior parties. However, interpretations of the compositions are difficult to decipher. In “Binawiigo,” I chose two pictographs found on a lake in Ontario. The exact meaning of these two images – a human form and a wolf – is unknown. But it reminds me of the origin story about Original Man and Ma’iingan (Wolf). However, the human form also reminds me of Nenabozho. Nenabozho was a shape shifter and often transformed himself into a waabooz (rabbit). The long ears on the human figure seems to indicate that it is Nenabozho who has partially transformed. Misko Magoodaas (Red Dress) Watercolor / Gouache We usually associate MMIW (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women) with events happening today. But, it didn’t begin on dark, desolate highways. MMIW has existed ever since the Invasion and the colonization of our homelands. The fur trade wasn’t just about economic motives for tribes. It was also about the servitude of Native women as “country wives.” And, women forced into prostitution at forts and trading posts. Rape, beatings, and murder became the fate of many of these women. “Misko Magoodas” is about one of those victims – a woman who has been raped. She has cut off her braids as a sign of her grief. Her mirrored reflection in a red strap dress signifies her journey into the cauldron of historical trauma. Niibinishi Gabeshi (Summer Camp) Watercolor / Gouache The Ojibwe were a semi-nomadic people who followed seasonal rounds to areas of subsistence. The two main camps were the niibin (summer) camps and biboon (winter) camps. Daagwaagin (Fall) and ziigwan (spring) camps were more short-term and limited to gathering manoomin (wild rice) in the fall and ziinzibaakwad (maple sugar) in the spring, and late spring and early fall was a time for ceremonies. Niibinishi Gabeshi (Summer Camp) included a variety of activities – gathering birch bark, gathering plants for food and medicine, hunting and trapping, netting fish, growing food, and tanning hides for winter. The summer wiigiwam usually differed from the winter lodge in that reed mats were used for the walls. The wiigiwam provided protection from the elements yet was ventilated and cool on hot summer nights. Basswood twine was used to secure the roof and walls to frames made from ash saplings. Logs on the sides further secured to roof to the frame. Small A-frame structures were built to store various implements. Pits were dug, lined with birch bark with birch covers to keep foodstuffs cool and out of reach of animals. Rock mortars and pestles were used to grind mandaamin (corn). Small garden plots were common and planted with agasimaan (squash), mashkodesiminag (beans), and mandaamin (corn). Historians of colonization portray tribal life as drab and tedious. However, tribal peoples didn’t, like the colonizers, dominate nature; rather, they were dominated by nature. They lived a wholesome existence that was in balance with the Original Instructions mandated by Gichi-Manidoo (the Creator). Maamiikwendamaw Nagawbo (Remembrance – Boy in the Woods / Patrick Robert DesJarlait) Watercolor / Gouache My father’s Ojibwe name was Nagawbo because he was always in the woods and observing the things around him. He was also given another name – Gwiwizens Odayn Ozhibii ignaak (Boy with a Pencil). He is often attributed as the first Native American modernist in fine arts. But his artistic abilities weren’t limited to fine art. He was also a commercial artist who worked for ad agencies in Minneapolis in the 1950s and early 60s. His most famous creation was the Hamm’s Beer Bear. As a tribute to my father, I’ve painted the bear in his favorite pose – dancing on a log. But rather than a pine log, I have him dancing on a birch log to emphasize his connection to the Ojibwe. And, I’ve given him an update with an otter turban and bandolier bag. The ogaa (walleye) never appeared in the cartoons. So, I’ve added an ogaa to emphasize my father’s connection to Red Lake where our ogaawag are the filet mignon of the Ginoozhe-Aki (the Fish World). Wiizhaandige Gitigaan (Unfinished Garden) Watercolor / Gouache “I want us to be doing things, prolonging life's duties as much as we can. I want death to find me planting my cabbages, neither worrying about it nor the unfinished gardening.” ~ Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) Quotes, sayings, and phrases provide inspiration for cancer survivors. They become embedded in one’s thoughts and perspectives. For me, Montaigne’s narrative about unfinished gardening strikes a deep chord. It speaks to me about continuing life’s journey and attaining goals within our grasp. My death will find my garden unfinished, but that matters not. What I’ve accomplished is what is important. “Unfinished Garden” then is about my cancer journey. Several of the floral and leaf motifs have a personal meaning. A manidoog floats near me, a shape with translucent wings and a red bead representing the spirit being. The unfinished garden is symbolized by the large leaf that is near the center. Half of the leaf is finished, half is unfinished. Life’s end becomes an unfinished garden. Giiwosewinini (The Hunter) Watercolor / Gouache Biboon was a time for hunting waawaashkeshiwag (deer), moozoog (moose), and adikwag (caribou), and for trapping fur bearing animals. For women, indoor activities included making food utensils and birch bark food containers, and making clothing and moccasins that were often intricately decorated with dyed porcupine quills. Biboon was also a time for learning. Origin and Nenabozho stories were told to teach children their history, spiritual beliefs, creation of the natural world, and cosmology of the Anishinaabeg people. Many camps were located near rivers to allow access for ice fishing. The outside walls of the wiigiwanan (lodges) were covered with birch bark sheets that provided protection from the cold winds of winter. Abagwe`ashk (Catttail) fluff or moss was placed between the inner walls of reed mats and outer birch walls to provide insulation. “Giiwosewinini” depicts a hunter returning with a small waawaashkeshi (deer) that will help feed his village. The gijigaaneshiinzhi (black-capped chickadee) is the bird of winter who is able to survive sub-zero temperatures. He represents the spirit of the Anishinaabeg who, like the bird, are able to survive the harsh conditions of Biboon. Mitigwaakokwi Inoodewiziwin (Woodland Family) Watercolor / Gouache The family in this painting represents the contemporary generation of the ancestors who are depicted in the paintings of traditional life. They are the people of the Seventh Fire. In our Seven Fires Prophecies it is said: “In the time of the Seventh Fire New People will emerge. They will retrace their steps to find what was left by the trail. Their steps will take them to the Elders who they will ask to guide them on their journey.” They are the New People who have survived genocide, linguicide, ecocide of their homelands, forced assimilation, institutionalized racism, historical trauma, and intergenerational trauma. They are retracing their steps back to their language, cultural practices and beliefs, and traditional activities that define Ojibwe identity. It is a long path back but they are finding what was left by the trail. © 2019, Robert DesJarlait

2 Comments

9/20/2023 12:16:44 am

I think my blog also got a kinda cool comment form. A very nice.

Reply

12/10/2023 10:46:13 pm

https://turkeymedicals.com/hair-transplant

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRobert DesJarlait Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed