|

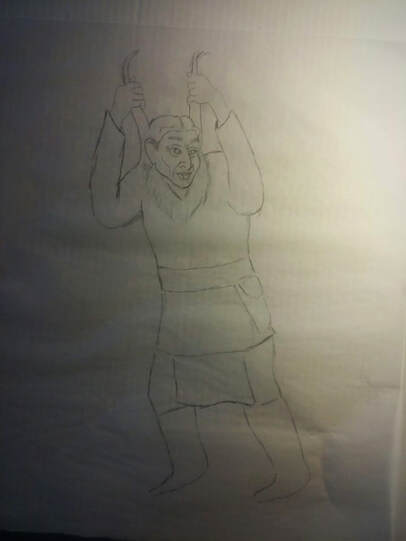

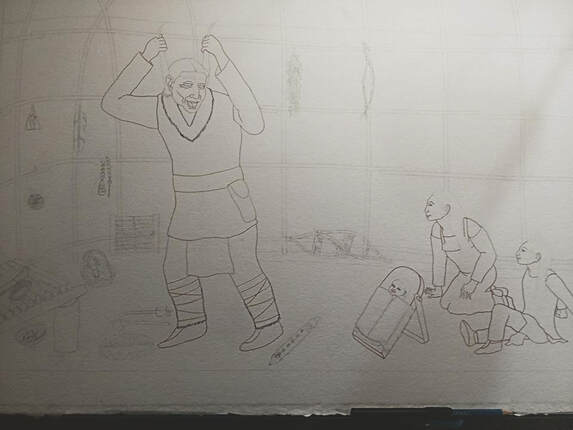

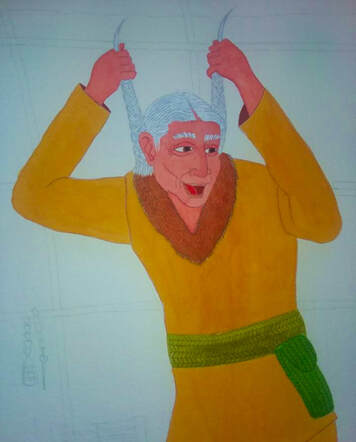

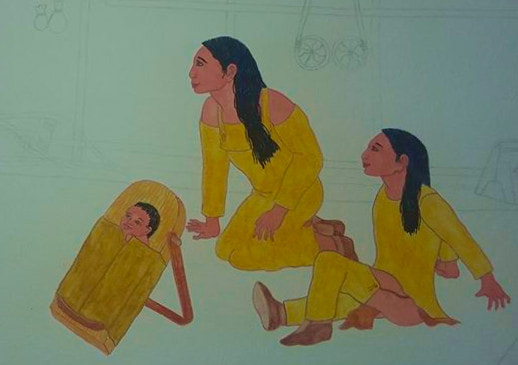

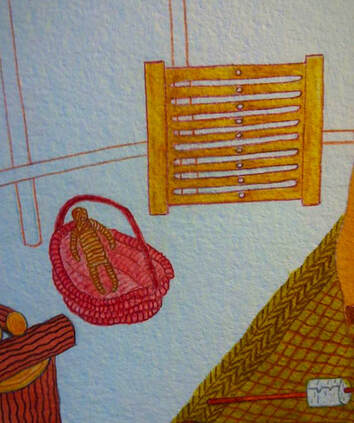

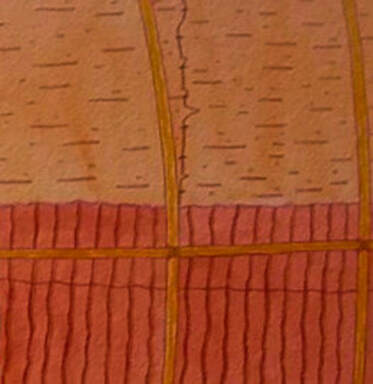

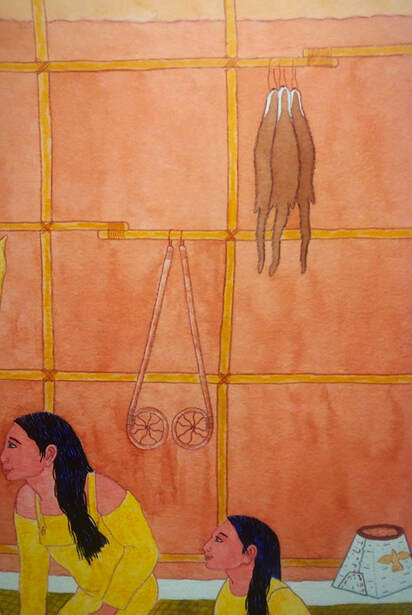

In conjunction with my current solo exhibition (“Ojibwe Manidoowiwin,” AICHO Gallery, July 11-Sept 10), I’ll be writing a few articles related to the art. This first article focuses on the process of making art – some of my concepts regarding my art and looking at one of my works - from initial sketches to the finished work. Concepts and Visions I’ve written elsewhere about the meaning of Ojibwe Manidoowiwin. Ojibwe Spirit, i.e., Ojibwe Manidoowiwin, is based on Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious (kollektives Unbewusstes). Jung wrote: “And the essential thing, psychologically, is that in dreams, fantasies, and other exceptional states of mind the most far-fetched mythological motifs and symbols can appear autochthonously at any time, often, apparently, as the result of particular influences, traditions, and excitations working on the individual, but more often without any sign of them. These "primordial images" or "archetypes," as I have called them, belong to the basic stock of the unconscious psyche and cannot be explained as personal acquisitions. Together they make up that psychic stratum which has been called the collective unconscious. “The existence of the collective unconscious means that individual consciousness is anything but a tabula rasa and is not immune to predetermining influences. On the contrary, it is in the highest degree influenced by inherited presuppositions, quite apart from the unavoidable influences exerted upon it by the environment. The collective unconscious comprises in itself the psychic life of our ancestors right back to the earliest beginnings. It is the matrix of all conscious psychic occurrences, and hence it exerts an influence that compromises the freedom of consciousness in the highest degree, since it is continually striving to lead all conscious processes back into the old paths.” Ojibwe Manidoowiwin is, essentially, the Ojibwe collective unconscious. In terms of art, imagery is formed by tribal primordial images or archetypes. My art is but one aspect of Ojibwe Manidoowiwin. Visual arts, beadwork, quillwork, sculpting, carving and other art expressions are facets of Ojibwe Manidoowiwin. On another note, I can’t speak for all mazinibiigewininiwag (artists), however I think that most mazinibiigewininiwag, in particular those who have been doing art for a number of years, develop philosophies/concepts about what their art is about. It is the concept that sustains the artist in the creation of their art. The subject matter may vary, but there is a unifying concept that brings the imagery together. Art incorporates an artist’s concept of their art – what it’s about; the process expresses the concept through the painted imagery. However, an artist doesn’t sit before a canvas and consciously think about how s/he is going to express their concept. Rather, the concept is inherent within the artist and the art expresses an innate spontaneity of concept. But the concept isn’t necessarily static. Spontaneity allows for changes. Hence, the concept evolves yet remains rooted in the central core of the artist’s intuitive notion of her/his creativity. Another level of creating art is izhinamowin – vision. It may be a complete vision –Waaseyaabindamowin – in which the imagery is perspicuous when the artist begins his/her work. Or, it may be bawewin(an) – imagery revealed in a dream or several dreams. Sometimes it’s a combination of the two. The vision may be complete, yet bits and pieces may be revealed through dreams and waking visions as the artist creates her/his work. This is part of the spontaneity of concept. Essentially, a visual work is the fulfillment of the artist’s vision. Titles in Ojibwe When I first began doing my art, a number of pieces were titled in Ojibwe. Out of the 31 works in my first solo exhibit (1986), 16 were titled in Ojibwe. At that time, I knew very little about the language. What was the impetus for using Ojibwe titles? I wasn’t influenced by other Ojibwe artists. As far as I knew, other artists weren’t using Ojibwemowin. In the 1980s, language was stagnant. There weren’t any language programs. The Baraga dictionary and Nichols and Nyholm Word List book were the only sources for Ojibwe words. Albeit the language earning was limited, I had access to words. Using words for titles wasn’t simply because I wanted my art to be more “Ojibwe.” It had to do with the changes I was going through in my life. In 1982, I stopped drinking. Sobriety opened the door to engage in art. My sobriety marked a new life. It allowed me the opportunity to learn about traditional values and practices. The words, terms, and phrases of language enabled me to see the world through an Anishinaabe mindset. Ojibwemowin helped to give my world shape and form. It gave, and continues to give, shape and form to my art. N. Scott Momaday wrote: “A word has power in and of itself. It comes from nothing into sound and meaning; it gives origin to all things…We perceive existence by means of words and names. To this or that vague, potential thing I will give a name, and it will exist thereafter, and its existence will be clearly perceived. The name enables me to see it. I can call it by its name, and I can see it for what it is.” To name something in one’s language gives the word power. Words are medicine. Words can hurt or they can help. Words can heal. Every word has a spiritual meaning behind it. It is the spirit of the word where the power comes from. Each word is a spiritual instruction to Gichi-Manidoo, the Creator. Each word or phrase is a prayer and a request. When we say the word or in our thoughts, we are making a request. Gichi-Manidoo responds. We need to be aware of what we are asking for and to understand the relationship between the word and the spiritual instruction behind it. In relation to art, naming a work in Ojibwe gives it power. It gives origin to the images that I paint. It also provides an educational value. The viewer learns something about the language. In this regard, it keeps the language alive. Ma’iingan signature One of the distinguishing features in my art is my signature. I sign my name with the image of a ma’iingan (wolf) paw. I’ve always signed my work with a ma’iingan paw going back to my first artwork in 1983. I quit drinking in 1982. During that time, I had several lucid dreams. A recurrent dream was about a ma’iingan. It always seemed that the ma’iingan was trying to tell me something. But the meaning only became clear after several dreams. At first, the ma’iingan was alone. He wandered through the woods, curious and looking, observing the life around him – the plants, trees, waters, animals, and insects. He could have very well been the ma’iingan that journeyed with Anishinaaba – Original Man – companions who were separated by Gichi Manidoo to live their own lives when the Earth was new. In the dreams, he found a new companion, a female ma’iingan, with whom he fathered four cubs. Together, they lived in the forest and he became their protector. I related the dreams to my own life. Like ma’iingan, I journeyed alone. Then I met my companion. We didn’t have children during the time I had the dreams. But the dreams foretold that we would have four children. And in my role as a father, I would, like the dream ma’iingan, be the protector of my family. The ma’iingan is akin to a bawaagan (guardian spirit animal). In my new life as a young husband and a father-to-be in the near future, the ma’iingan bawaagan provided me with a sense of direction and guidance. And, it is for this reason, why I sign my name with the paw of a ma’iingan. Aadizookewinini (Storyteller) Aadizookewinini (Storyteller), 22" x 30," Watercolor/Gouache, 2020 This is my first sketch of the storyteller. I always sketch on tracing paper. Tracing paper allows me to flip the paper and see if the proportions are correct and make corrections (on both sides of the paper) if needed. Basically, the original sketch is reworked and becomes the final sketch. Details such as hair, fur, belt, pouch, etc. are added once I begin to paint the figure. I did the sketch of the children's group on a separate sheet of tracing paper to allow for positioning. At this point, I've moved from tracing paper to the medium for the painting - a 30" x 22" cold press, watercolor sheet of 300 lbs paper. I moved the dikinaagan (cradle board) to the front of the two children. I sketched in several of the items that are inside the wiigiwam. One of the things I wanted to emphasize in this painting was the inside of a wiigiwam (birch bark lodge).They were built to accommodate the size of the family. As such, they could be fairly spacious and allowed for items to be stored on the walls and the perimeter of the walls. Although it's nor depicted, a hearth is located at the center of the lodge. The first image I paint is the storyteller. The central figure is always first when I paint. I mix my skin tone and paint his face and hands. For consistency, I cover and save the skin tone paint for the children. After painting in the skin tone, I work my way down beginning with the hair, then fur collar, shirt, leggings, and apron, biboon-makizin (winter boots); the last thing I paint is the waasechiganaatig (sash) and biindaagan (pouch) that are made from reeds. After finishing the storyteller, I paint the group of children. I do all the skin tones first. Then I do the young boy, followed by the girl. The baby and cradle board is last. To complete the storyteller, I painted the items he uses to tell his stories. This detail shows his dewe'igan (hand drum), deyewe'iged (drum stick), and zhina'oojigan (rattle). Detail of storyteller's bibigwan (flute). To complete the central figures (storyteller and children), I paint the gaasiizideshimowin (floor mat). The next step is painting the desa'on (lodge platform), followed by the opwaagan (pipe), mishiikewi-dashwaa (turtle shell), and bagesewinaagan (dish game). Detail of oziisigobimizhii-makak (willow basket), asigobaani-mazinichigan (basswood bark doll), and okaadeniganaatig (loom - this particular loom is an Ojibwe heddle loom used to weave sections for reed mats) My next step is to paint the interior of the wiigiwam - abanzhiiwaatigoon (lodge poles), wiigwaasabakwaan (birch bark roof) and aasamaatigoon (inside walls). Detail - asabikeshiinh (dream catcher), bigiiwizigan (maple sugar taffy/candy), nabaa'waaganag (ring and toss game), giniw-miigwan (golden eagle feather). Detail - aagimaakwan (snow shoes), gamaagiwebiinigewin (snow snake game), wiingashk (sweetgrass), mashkodedewashk (sage). Detail - baaga'adowaanan (lacrosse sticks), nigigwayaanag (otter hides), and makak (birch bark container). Art and Text © 2020, Robert DesJarlait

2 Comments

1/11/2023 07:38:55 am

Very nice article, I found it very useful .Even I have this wonderful website, Good quality of windows and doors are very essential for any workplace. They provide top quality windows and doors and offer these services at very reasonable price.

Reply

1/11/2023 08:29:28 am

The concept is inherent within the artist and the art expresses an innate spontaneity of concept. But the concept isn’t necessarily static. Spontaneity allows for changes. Thank you, amazing post!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRobert DesJarlait Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed