|

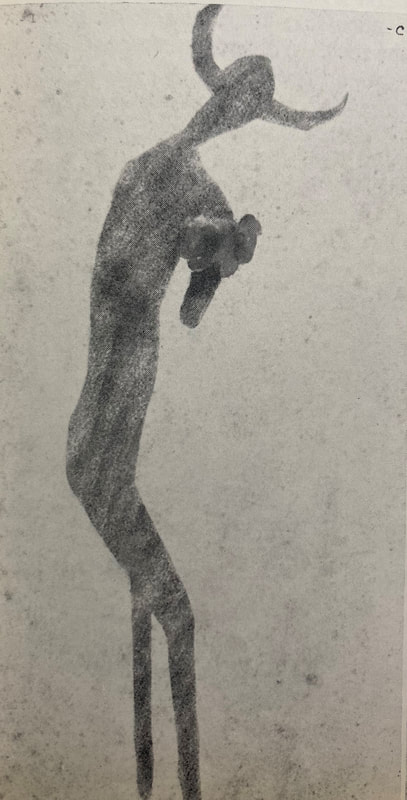

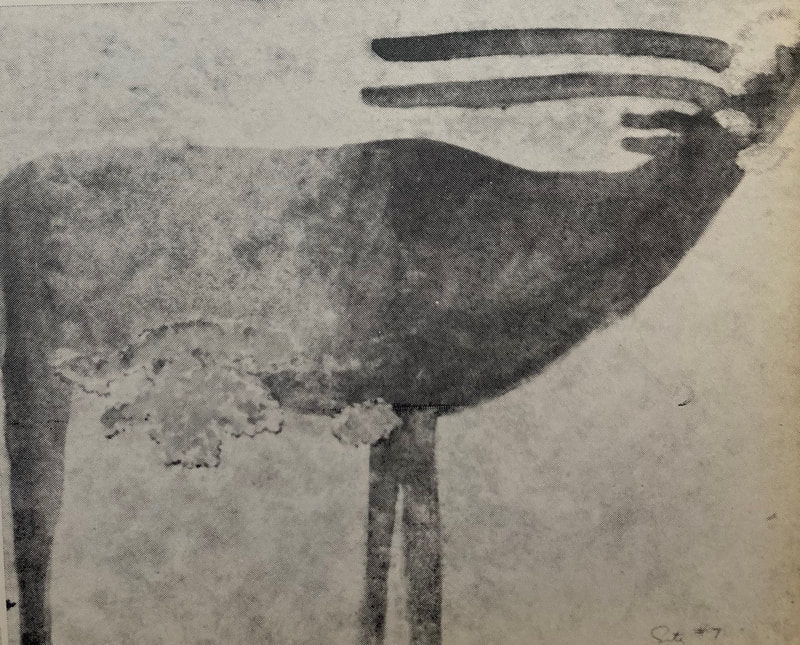

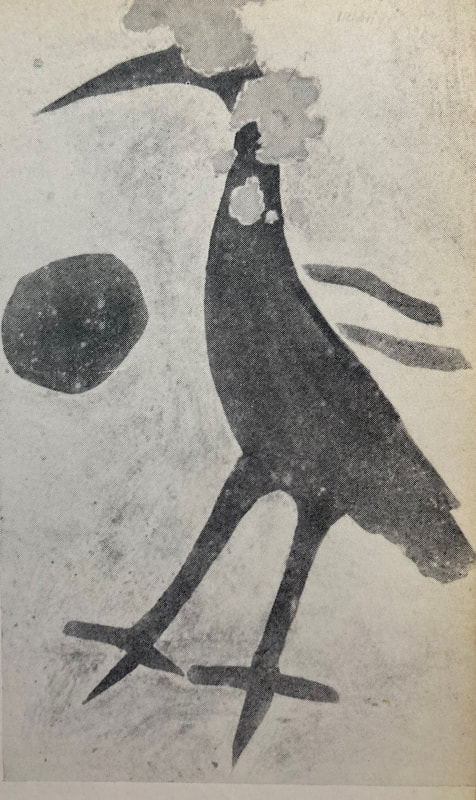

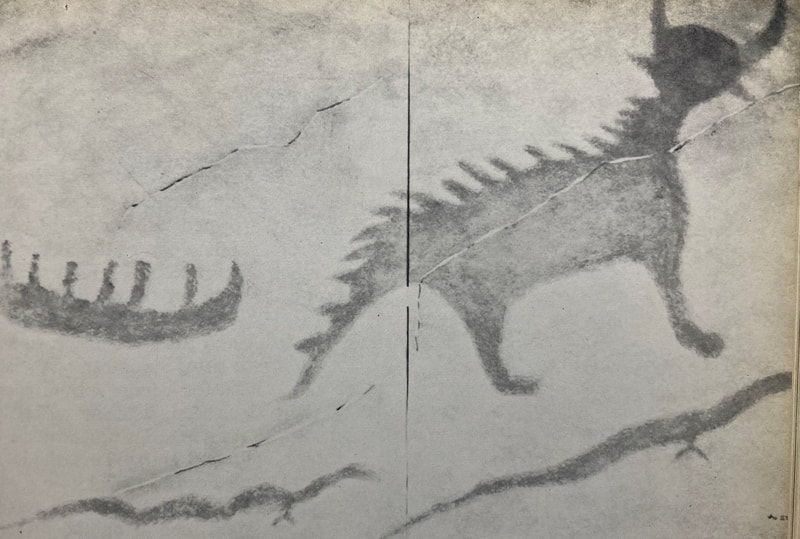

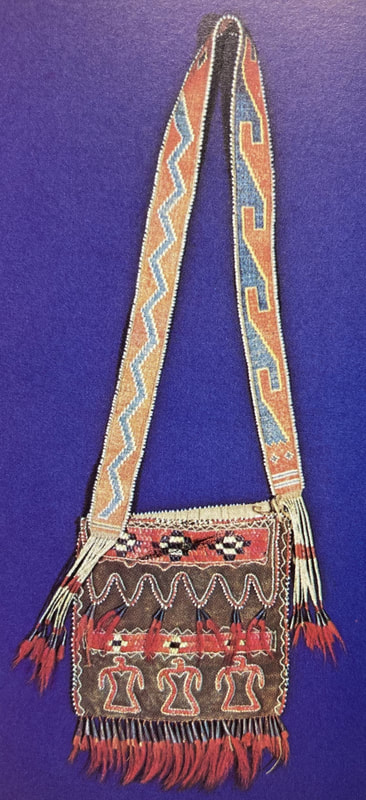

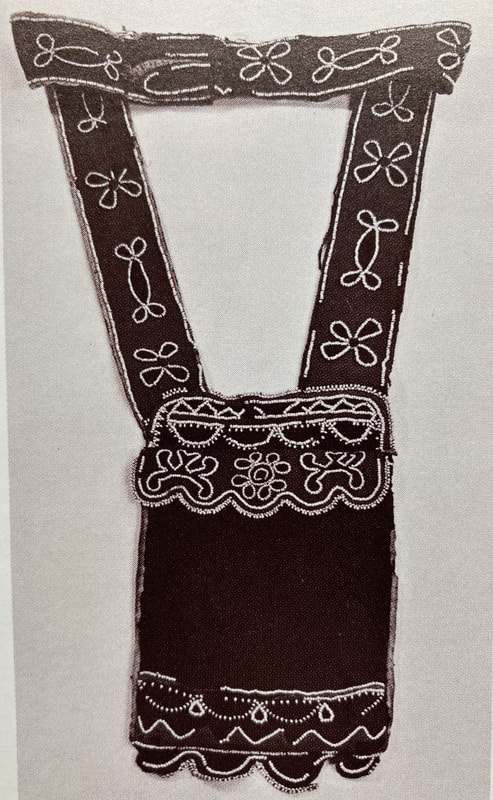

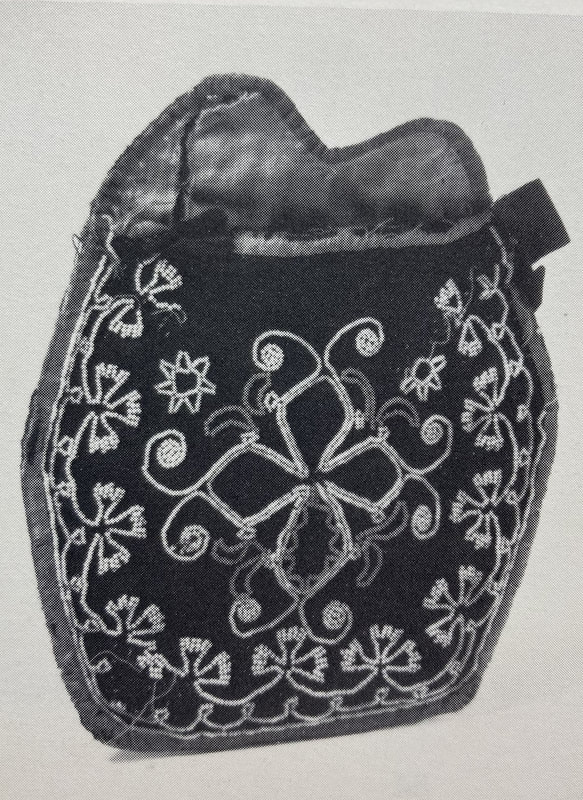

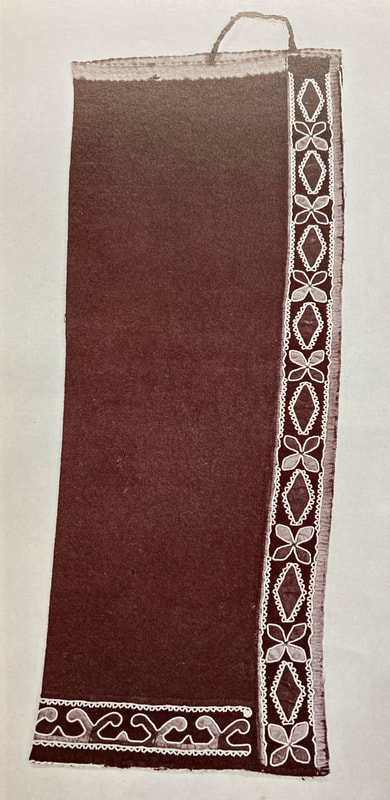

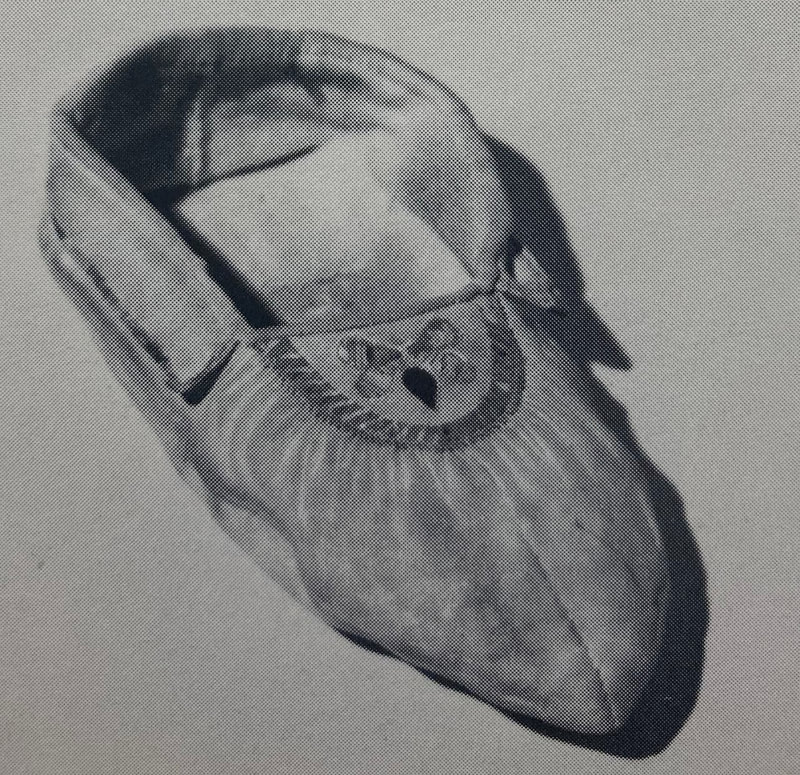

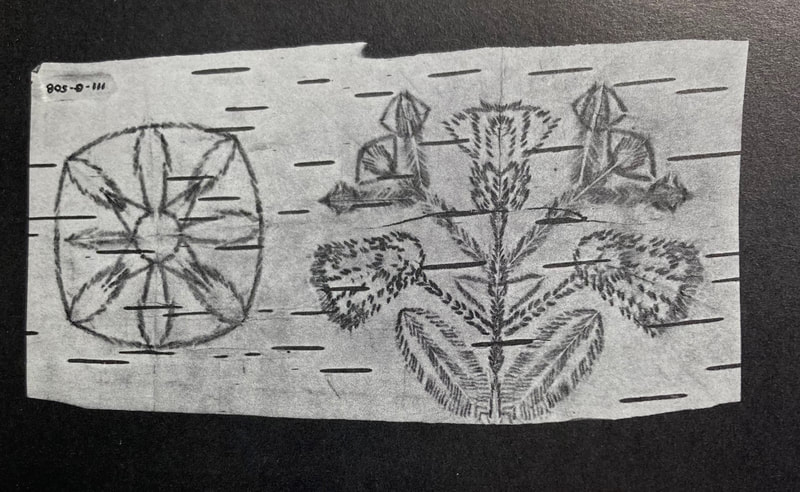

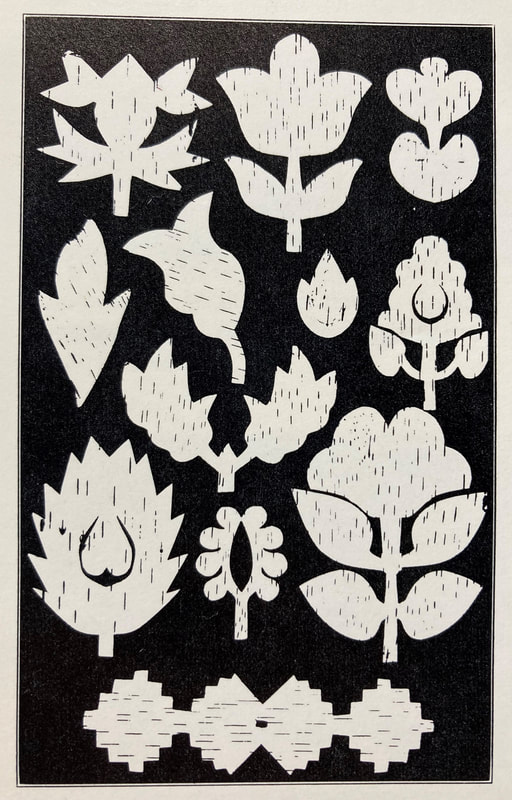

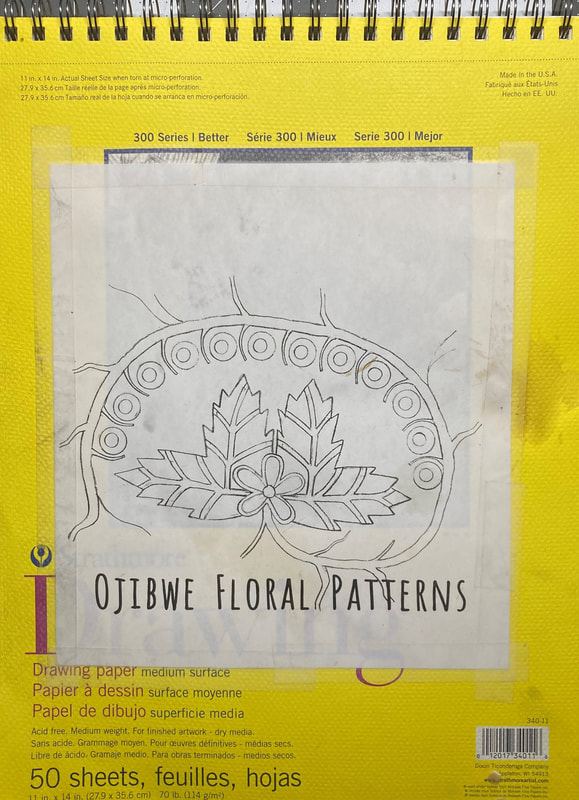

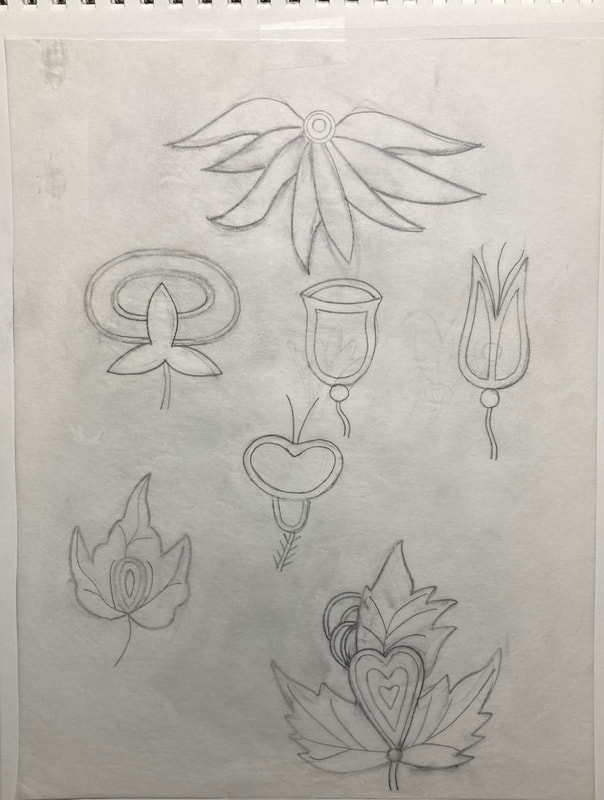

I once read that the floral motif on makizinan (moccasins) faced the wearer and not the observer. The observer viewed the art that one wore. The positioning of the floral motif on the makizin was not happenstance. The floral apiinwe’igan (vamp) was positioned to innately connect the wearer of the Woodland environment in which s/he lived. The apiganegwaajigan (cuff) was embroidered with floral motifs that encircled the foot of the wearer and firmly rooted them to Gookomisakiinaan (Grandmother Earth). Floral mazinigwaaso (bead embroidery) was not limited to makizinan. It flowed upward and took shape and form on leggings, aprons/breechcloths, vests, yokes, shirts, dresses, and bandolier bags. Such clothing was for gatherings and social dances. When worn, the wearer became the personification of Anishinaabe identity. Makizinan were, however, worn daily, and the floral motifs provided a consistent connection to one’s identity and environment. To understand Anishinaabe mamazinibii’igewin (art), one needs to view Anishinaabe aesthetics from an Anishinaabe worldview. In this worldview, there is no separation between art forms; rather there is a continuity of aesthetics, although the medium differentiates the application and expression of those aesthetics. Anishinaabe mamazinibii’igewin (art) began as pictographic images painted or etched on rock. Anishinaabe writer Gerald Vizenor provides a more expressive definition of pictographs – pictomyth: the believable Anishinaabe pictures of myths or believable Anishinaabe myths of pictures.[1] Such art existed long before the European invasion of North America. The rock pictomyths focused on the relationship between humans and the aadisookaanag, i.e., other than human persons: the Four Winds, Sun, Moon, Thunderbirds, “owners” or “masters” of species of plants and animals and the characters in myths – collectively spoken of as “our grandfathers” or ancestors.[2] Lake Superior and Canadian Shield tracings on rock pictomyths / Selwyn Dewdney Lois Jacka writes: “As skills were passed down through the ages, new materials became available, new techniques developed, and each succeeding generation contributed its own interpretations and innovations.”[3] This was apparent with the advent of drawing or etching pictomyths on birch bark. Like the individual aesthetics with its focus on content rather than form on rock pictomyths, the development of birch bark pictomyths expressed a group aesthetics that was cultural in form yet emphasized content. Birch bark pictomyths were a cultural mode of communicating and recording history, migration, ceremonies, traditions, stories, and songs. Hence, Anishinaabe mamazinibii’igewin (art), in its earliest forms, was a means of communication. The form itself conveyed the message. However, the imagery of the form expressed a group aesthetic. The importance here is the continuity of the images. Images that began on rocks, then on birch bark, began to be used as a group aesthetic. Wooden spoons, ladles, and bowls, birch bark containers and baskets, woven reed mats, and yarn bags were decorated with pictomyths. Such imagery carried over to sashes, moccasins and clothing that were decorated with quillwork. As such, Anishinaabe images had a decorative, i.e., aesthetic, intent that provided a confluence of art and identity. The main media for traditional art was gaag (porcupine) quills and mooz (moose) hairs. Dyes were obtained from barks, roots, leaves, flowers, and berries and used to color quills and animal hairs, including various fibers. Geometric quilled images depicted the individual’s clan affiliation and dream symbols. Abstracted motifs of animals, flowers, insects, and leaves were common in quillwork. Quillwork tended toward abstraction or geometric designs because of the rigidly of the quills. The influx of colored seed beads in the 1860s led to significant changes in designs. Carrie Lyford notes: “The Ojibwa introduced the curvilinear pattern into the western region adopting and embellishing it to their fancy.”[4] From the curvilinear pattern, Anishinaabe artists developed a symmetrical double curve motif that curved out from a central point. The opposing curves were decorated with leaves, buds, and flowers that were also arranged symmetrically. Stylistically, floral imagery developed as an art that was largely representational. Leaves tended to be realistic, but flowers could difficult to identify. Many floral patterns shared similar shapes but were differentiated by colors. But there was also much variety in the way flowers were depicted. Some flowers were in profile and offered an “x-ray” view, i.e., one could see inside the flower. Others were depicted with a ¾ overhead angle view. The color palette was rich with color and hues. Two techniques were employed in the application of beadwork. Bead weaving was done on a loom or beads were embroidered on broadcloth or velvet. On breechcloths, the design was symmetrical. On leggings, the symmetrical pattern was split - the design on the left leg matched the design on the right leg. On vests, the front panels followed the same pattern as leggings. The pattern on the left side matched the pattern on the right. On the back of the vest, the pattern was symmetrical. The most elaborate beadwork was gashkibidaaganag (bandolier bags) that were largely worn by men, and to a lesser extent, by women. The large beadwork front piece panel and strap panels were woven on looms or embroidered on fabric. The patterns on the front panels and straps were usually asymmetrical. Gashkibidaaganag designs were either fully geometric or floral. Some gashkibidaaganag combined geometric designs on the straps and floral motifs on the panels. Making gashkibidaaganag was the providence of Anishinaabekweg (Anishinaabe women). Indeed, Anishinaabeg mamazinibii’igewin (art) itself was largely the providence of Anishinaabekweg and was rooted in the pre-contact period. Floral patterns and designs were passed to subsequent family generations. The artists were innovators of style. Each had their own distinctive style of depicting flowers and leaves. There isn’t a precise number for how many artists were creating beaded floral art, but quite often their particular style was associated with where they were from. Red Lake differed from Leech Lake, Leech Lake differed from White Earth, White Earth from Mille Lacs, etc. Marcia Anderson notes: “When the form defined as a gashkibidaagan (bandolier bag) first emerged in the mid-nineteenth century and perhaps earlier, it was, I maintain, the Ojibwe of Minnesota who gained the distinction of being the most accomplished practitioners of this art…Gashkibidaaganag have been the singular and most visually significant art and craft of the Ojibwe.”[5] Bandolier Bags, Men's Apron, Leggings, and Moccasins, ca 1880s-1890s Francis Densmore noted that Anishinaabe manidoominens-omamazinibii’igeg (bead artists) had a box of patterns cut from birch bark. These patterns were combined in forming designs and mainly used in applied beadwork. The patterns could also be used for etching on birch bark and other decorative work. In the pre-contact period, “the pattern was pricked in birch bark with a sharp fishbone, the pricks being placed close together, after which the bark was cut along these lines with a knife.”[6] Mazinibaganjigan (Birch bark biting) was another technique for an Anishinaabe omamazinibii’ige (artist) to collect and catalog their patterns. Using a thin sheet of birch bark that was folded, the artist bit their design into the bark. Birch Bark Bitings, ca 1879 / Birch Cutouts, ca 1910 Today, the work of Anishinaabe manidoominens-omamazinibii’igeg (bead artists) whose media focuses on quillwork, beadwork, and appliqué work provide continuity to the aesthetics and floral motifs that are strongly rooted in the past. Some have gone from traditional representational floral forms to depicting more realistic floral forms. The aesthetics of Anishinaabe mamazinibii’igewin (art) has transitioned to fine art. “Today’s painters tell stories of the past [and present] in a vast array of media, including oils, pastels, prisma, watercolors, egg tempura, and more. Spiritual figures [and pictomyth figures], traditional symbolism [and designs and motifs], and scenes from everyday life fill canvases by the score, yet each artist’s work is different.”[7] On canvases, artists depict symmetrical floral designs. Graphic artists use iPads and Procreate to create digital imagery depicting an array of floral patterns. In turn, such designs are used on posters and flyers for community events and powwows and logos for groups and organizations. And designs are used to embellish clothing – hoodies, t-shirts, sweaters, pants, and sneakers. Like our ancestors, we have clothing that provides us with a sense of culture and identity. Contemporary Anishinaabe omamazinibii’igeg (artists) who create floral forms on canvas or graphic illustrations connect to a popular form of art – flowers. People love flowers. Art prints of botanical art or floral art bloom on the walls in many households. Flower art has a long history. Blossoms, blooms, bouquets have been depicted in art, worldwide, since ancient times. Huaniaohua – bird and flower painting - began in China in 4000 BC. The subject matter also included insects and fish. It was considered as a specific genre of Chinese art. “Artists not only directly portrayed the outer beauty of flowers; they also expressed the subtle spirit and demeanor of their subject. Painters went even further to imbue blossoms with deeper meaning, transforming them into objects for lodging feelings.”[8] Huaniaohua was introduced to Japan during the 10th century where it developed into a genre called kacho-e – bird and flower painting. Whereas Chinese artists included insects and fish, Japanese artists focused on birds and flowers together. In the 15th century, kacho-e became a subset of ukiyo-e, woodblock painting. Japanese artists expanded their oeuvre to include insects and fish. “[T]he development of (kacho-e) paintings of plants and flowers were made for aesthetic reasons and to give pleasure to others rather than for the scientific reasons normally associated with botanical art.”[9] “In the Western world, botanical illustration dates to the 1st century B.C., when the Greek physician Krateus began depicting herbal plants with scientific precision. Botanical illustrators portrayed the ideal version of every plant, erasing any leaf holes or petal folds. To do so, they studied example after example of the same floral species, before combining their findings together into one archetypal drawing.”[10] In the 16th century, Dutch artists broke away from botanical art tradition, developed their own aesthetics, and painted monumental sized still-life work. During the 19th century, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists painted flowers in their work; still-lifes were a sub-genre subject. Ukiyo-e (Japanese woodblock art) influenced the Impressionist works of Renoir, Monet, Degas, Pissarro, Cassatt, and Manet; and, Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Seurat. In addition to floral forms, Japanese art influenced Impressionist/Post-Impressionist subject matter, perspective, composition, and color. Van Gogh used the term Japonaiserie to define the Japanese influence in his work. Modernist painter Georgia O’Keeffe was best known for her large, close-up flower paintings. Her oeuvre included 200 paintings of plants. “When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world for the moment,” O’Keeffe once said. “I want to give that world to someone else.” Often considered the mother of Modernism, O’Keeffe transformed the still life painting into a radical event. Her close-up views of flowers bordered on abstraction, and challenged viewers to slow down and enjoy the process of careful observation.[11] Obviously, the genre of floral art has impacted diverse cultures and art movements. Among Native cultures, floral art was, and is, expressed through beadwork. The transition of Anishinaabe floral aesthetics to fine art is exampled by the work of my father, Patrick Robert DesJarlait (1921-1972). Bill Anthes notes: “DesJarlait’s paintings have been compared by some writers to traditional Ojibwe artworks, such as birch bark scrolls, beaded bandolier bags…which feature geometric and floral patterns. In a 1945 statement, he (DesJarlait) wrote, “I think my color and design comes from the Indian craftwork such as beadwork and porcupine quillwork which I have seen all my life.”[12] From the 1980s onward, waabigwan mazinibii’iganan (floral designs) have always been a part of my work when I’ve depicted images wearing beadwork. In 2014, I began exploring the idea of using waabigwan mazinibii’iganan as a part of the composition. I did a watercolor pencil illustration titled, “Niimi-Bagosenjige” (Dance of Hope), featuring a jingle dress dancer surrounded by waabigwan (floral) motifs. The designs were from a file folder on my computer. The folder contained photographs of bandolier bags, dance aprons, leggings, and moccasins, circa 1870-1900, that I had downloaded from the Internet and exhibition books. Niimi-Bagosenjige (Dance of Hope) In 2015, I decided to compile the photographs in the folder as line drawings. I cataloged over 150 individual old style floral designs. Old style floral designs here are defined as motifs from 1880-1900. The personal reference book I put together, “Woodland Floral Patterns,” allowed me easy access to a wide array of designs I could use in my work and to explore ideas using floral motifs. In 2019, I did three works that integrated floral motifs into my compositions. The first was “Manidookewin” (Ceremony) which featured several floral designs in the foreground. They were part of the environment that I depicted in the painting. As foreground images, they were closest to the observer. The second piece was “Zaazegaa-ikwe miinawaa Biibiiyens” (Gentlewoman and Baby). This painting features three maple leaves changing in fall colors. Next to the mother and child is a birch bark container with several flowers rendered in Anishinaabe floral style. The third work, “Wiizhaandige Gitigan” (Unfinished Garden), is a self-portrait that conveys my experience after two battles with cancer. The image is surrounded by an array of floral motifs. One leaf is partly painted with the remaining part outlined in a light gray. It represents the unfinished part of the floral garden and provides a visual metaphor for life as an unfinished garden. Manidookewin (Ceremony) Zaazegaa-ikwe miinawaa Biibiiyens (Gentlewoman and Baby) Wiizhandige Gitigan (Unfinished Garden) In 2023, I wanted to explore the idea of floral motifs becoming the art itself. Of course, this wasn’t an original idea. As mentioned beforehand, it has been done by others. I was looking for something different, something to set it apart from others. The first work in the Mitigwaki Waabigwaniin Okogiwag (Woodland Floral Bouquet) series features a center vine with several floral motifs attached to the vine. I added an oboodashkwaanishiinh (dragonfly) to reflect the floral environment. However, I wasn’t satisfied with the composition. The floral design was too much like floral designs depicted by other artists. I then came up with the idea of creating an asymmetrical floral bouquet with an aniibish (leaf) as the anchor image and floral motifs attached to a strong biimaakwaad (vine of life). I added manidooshag (insects) to the composition; in one work, I put in a nenookaasi (hummingbird) since they are part of the floral environment. Each work was rendered with Caran d'Ache watercolor pencils on 11 x 14 archival paper. Each was titled after the insect (or bird) featured in the composition. The Mitigwaki Waabigwaniin Okogiwag series began with the notion that floral art is a popular art form. And, that was proven to be true. At the 2023 Anishinaabe Art Festival, my floral prints were my top seller. I plan to continue the series but with a change in medium and media. For the next step, I’ll be using opaque watercolor (gouache) on 16 x 20 watercolor board and produce a series of six paintings. They will be part of my solo exhibition that is planned for late 2024 or early 2025. The importance of contemporary waabigwaniin mamazinibii’igewin (floral art) is it conveys an evolving individual aesthetic that is rooted in the art of the traditional past. Like the pictomyths that were created when the Earth was new, modern pictomyths communicate traditions, stories, and teachings. Indeed, waabigwaniin mamazinibii’igewin incorporates the teachings of the Four Orders of Life – Aki (Earth), Mitigoog/Gitigaanan (Trees/Plants), Awesiinyag/ Manidooshag (Animals/Insects), and Anishinaabe (Human Beings). Human Beings, who are the last in the Four Orders, have the responsibility to ensure survival and harmony of the other Three Orders. Waabigwaniin mamazinibii’igewin is a visual metaphor that embraces our relationship to the Three Orders of our environment that provides bimaadiziwin (life). Note: The Anishinaabemowin terms – Mamazinibii’igewin (Art) and Omamazinibii’ige(g) (Artist/Artists) - are from Ningewance, Patricia M., “Pocket Ojibwe: A Phrasebook for Nearly All Occasions,” Mazinaate Inc, 2009. Works Cited

©Robert DesJarlait, 2023

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRobert DesJarlait Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed