|

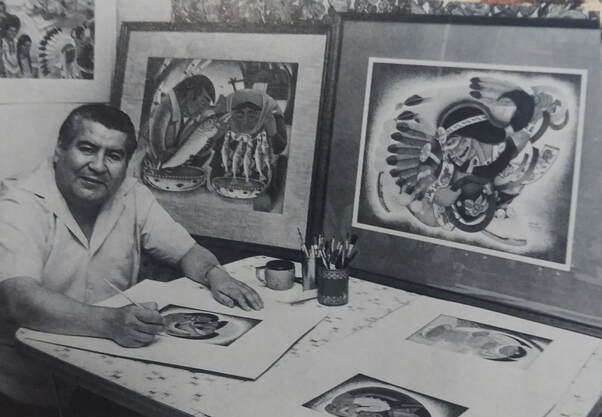

Red Lake Ojibwe artist Patrick DesJarlait circa 1971. (Photo courtesy of Robert DesJarlait) Dalton Walker

Indian Country Today There's more to this story than a box of butter. One version starts when Land O’Lakes quietly removed “Mia,” the face of its butter since 1928 from its boxes. Company president Beth Ford said in Feb. 6 news release that the new marketing campaign “needed packaging that reflects the foundation and heart of our 1/4 company culture - and nothing does that better than our farmer-owners whose milk is used to produce Land O’Lakes dairy products.” This was all done without fanfare. Where Mia kneeled for nearly a century, there is now an empty space. What remains is a logo and a lake with trees in the background. People picked up the new butter packages without much notice. Then the Minnesota Reformer, a digital nonprofit news source, reported the change on April 15. That story went viral and was posted by national media ranging from The New York Times to NBC’s Today show. The change was applauded by many in and out of Indian Country, including Minnesota Lt. Gov. Peggy Flanagan, White Earth Nation. “Thank you to Land O’Lakes for making this important and needed change,” Flanagan tweeted. “Native people are not mascots or logos. We are very much still here.” North Dakota state Rep. Ruth Buffalo, Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, told a Fargo Forum reporter that the image goes “hand-in-hand with human and sex trafficking of our women and girls … by depicting Native women as sex objects.” A week later Rep. Buffalo added on Facebook: “It is unfortunate the issue of Land O’ Lakes cooperative’s recent decision to phase out the ‘Mia the butter maiden’ logo on its packaging has been used in a divisive way. As an elected legislator in North Dakota and a Native American woman, I was asked for an opinion on this decision that was, as with most complex issues, distilled to a short quote.” Buffalo’s well-reasoned post explored issues ranging from using Native images in the multibillion advertising issue to the impact on popular culture. “We are not invisible people, and we no longer accept breadcrumbs or in this instance, butter for those breadcrumbs,” she concluded. “Let’s work together to make real, contemporary Native American women visible and value their work and contributions to today’s society. Let’s respect and value their voices even when we may disagree.” This is where the story twists because the legacy of Ojibwe artist Patrick DesJarlait goes well beyond Mia and Land O’Lakes. DesJarlait was employed by the advertising agency Campbell-Mithun in Minneapolis when he was given the assignment to market the farmer-owned cooperative. The original brand of “Mia” had been refurbished twice since its launch in 1928. DesJarlait was tapped to create a third version. He reimagined a more human character, adding detail to Mia’s face and floral motifs on her dress. Subtle changes that mattered. That was the brand that stuck for seven decades. But the real legacy of DesJarlait is his body of work, some 300 pieces of art across the U.S. in museums and private collections. For many, especially for Red Lake Ojibwe in Minnesota, DesJarlait’s artistry impact remains nearly 50 years after his death. The award-winning artist and U.S. Navy veteran died at age 51 in 1972 from cancer complications. “My dad’s artwork has been out there for so long, and there's so many people that just don’t even know about his beautiful artwork,” DesJarlait’s daughter Charmaine Branchaud said. “There’s a story behind that man. It’s a part of history. Now, we are making history again with Mia. She’s disappeared, but that doesn’t mean my dad’s artwork is going to disappear. She was just a little bitty part of it. He had a lot of accomplishments in his life.” DesJarlait’s son, Robert DesJarlait, 73, said he was initially glad that the stereotypical image was finally removed. Then, the power of social media reminded him of another side of the discussion that was overlooked. On his Facebook page, Robert said many Ojibwe people shared their perspective of Mia while growing up Native. “Basically, it was giving the previous generation a sense of almost empowerment to see a Native woman on a box of butter. It gave them a sense of cultural pride,” he said. “After seeing those posts, I said, ‘that’s right, that’s why my dad created this image to begin with’.” The design, besides Mia, shows a lake with two points of land that Robert DesJarlait said represented Red Lake and an area on the reservation known as the Narrows, where lower and upper Red Lake meet. Another homage, one that is hard to see on the products, on Mia’s dress are Ojibwe floral design patterns. My father was working it both ways - he was strengthening the Land O’Lakes name by placing Mia at the lake and he was integrating a deeper Ojibwe connection to the environment in which they lived. Trees and lakes are part of our identity. As such, his art, and Mia, was a visual reminder of our connection to our homelands,” Robert DesJarlait said in a Facebook post. Robert DesJarlait, who like his dad is an artist, said his father has never gotten the proper credit for his creations. In the early 1950s, Patrick DesJarlait created the bear mascot, Hamm’s Bear, that was a staple for Theodore Hamm’s Brewing Company for years. “He was breaking barriers when he was in commercial art,” Robert DesJarlait said about his dad. “When other Ojibwe people in Minnesota found out (about his success) as a Ojibwe artist, they were proud of that, too.” An autobiography by Patrick DesJarlait, along with author Neva Williams, was published in 1994. The book is about DesJarlait’s life growing up in Red Lake, his military career and his life as an artist. When he was a young boy, Branchaud said her dad went blind for about a year and traditional medicines by his mom slowly helped DesJarlait regain his vision. Learning that history about her dad and her grandmother, Branchaud went into a career in healthcare. In the Navy, DesJarlait’s art talent was utilized. First as an instructor in Arizona at the Poston Internment Camp for Japanese internees and later at the U.S. Naval Academy in San Diego where he created animated training films. Prints of DesJarlait’s art work are still available online via a website Branchaud helps manage. Branchaud, 65, remembers growing up and seeing her dad working on his craft at the table in their suburban Minneapolis home. “He was at the kitchen table, doing his tracing, then watercolors came out and voilà a beautiful painting in front of him,” Branchaud said. “Those are the kind of memories I have.” Over the April 18 weekend, Branchaud went grocery shopping and hit the dairy section and purposely looked for Land O’Lakes items. She found an unsalted whipped butter tub that still has Mia. She didn’t have much luck finding any signature items with the image. “No real butter, no butter, butter,” she said with a laugh. Dalton Walker, Red Lake Anishinaabe, is a national correspondent at Indian Country Today. Follow him on Twitter - @daltonwalker

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

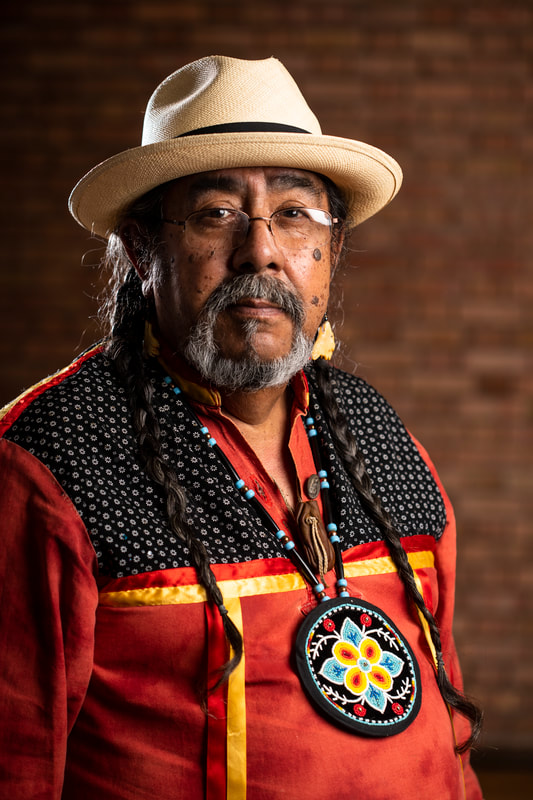

AuthorRobert DesJarlait Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed