|

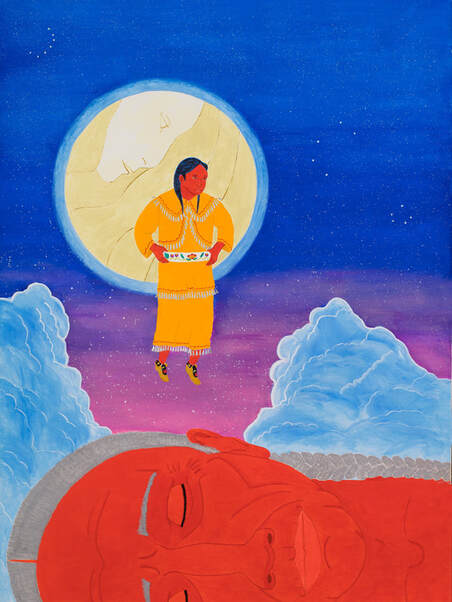

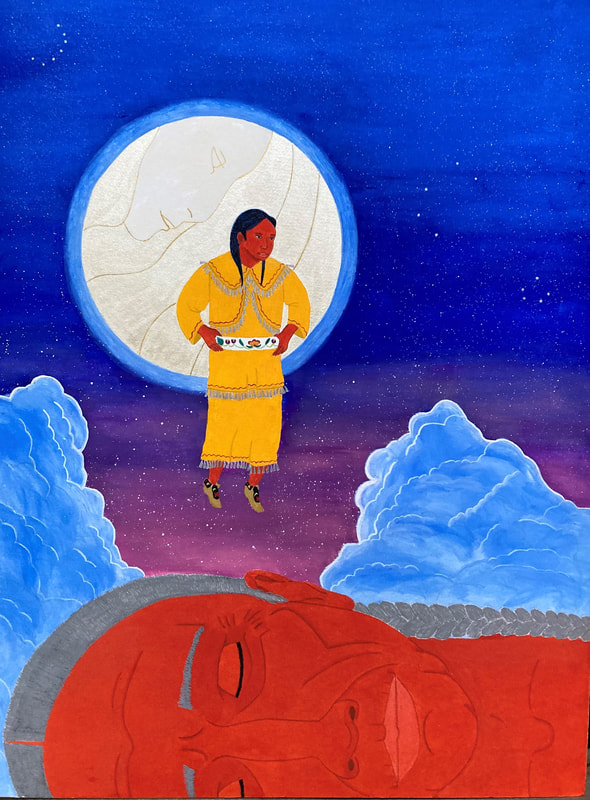

The Medicine Dance, 2022 by Thomas Peacock Sometimes at night when sleep takes me to that place where all things are possible and the earth and sky merge as one I dream and tonight, in a dream I hear the voices of old men long passed on to the spirit world gathered there among the sky spirits within the circle of the wolf’s trail and the path of souls and night sun there singing their voices high and in the familiar sing-song of the old time Ojibwe there around the drum their voices echoing off the big water and sky filled with stars too many to even wonder singing, singing then, in the forever sky my beautiful daughter there her hair and dark eyes there in her jingle dress she dances, head held high proud dancing, dancing © Thomas Peacock, 2022 Ziibaaska'iganagooday Bwaajigan (Dream Vision of the Jingle Dress) is part of "Those that have gone before us and all those yet unborn" Exhibition at AICHO Galleries, Duluth Minnesota. Thirteen artists were paired with thirteen writers. The writers were tasked with subjectively interpreting the art they were paired with. I'm grateful, and fortunate, that Thomas Peacock was chosen for my work. Gichi-miigwech Thomas for your beautiful words. A special miigwech to AICHO and CPL Imaging for providing the image. © Artwork, Robert DesJarlait, 2022

0 Comments

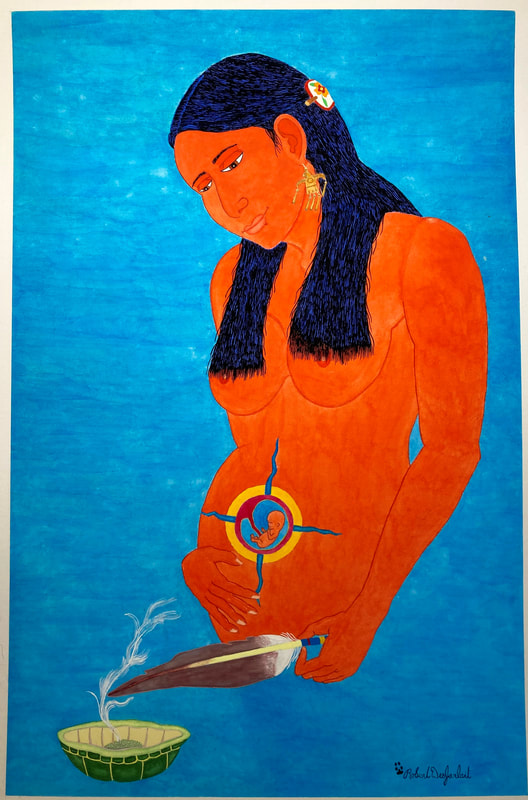

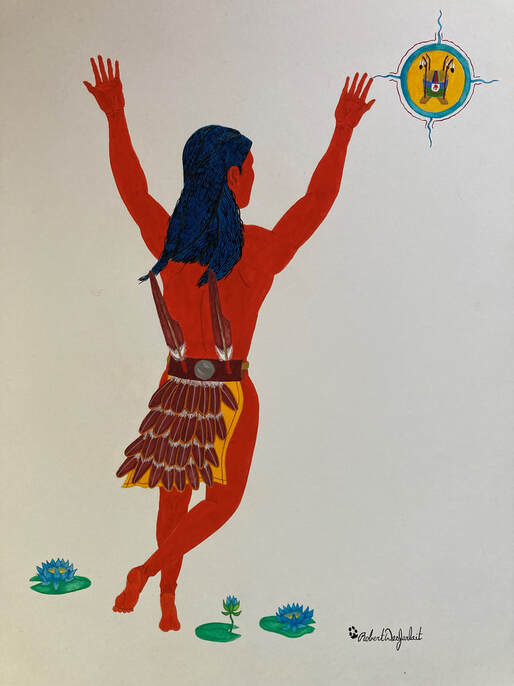

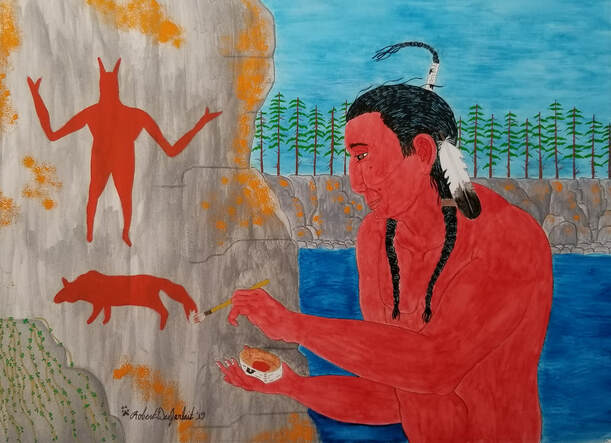

Miskwaasige Gichigami-Ojibwe (Red Sun-Great Sea of the Ojibwe) Gouache / Opaque Watercolor) on Watercolor Board

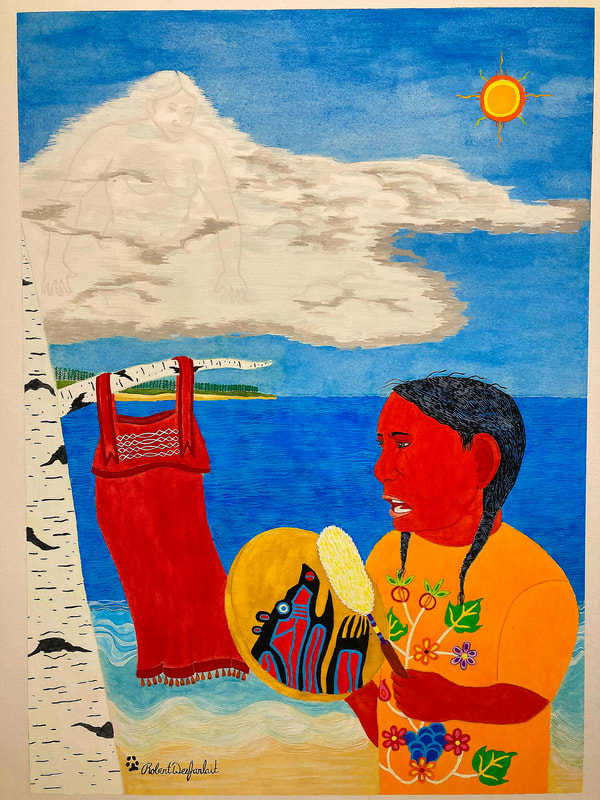

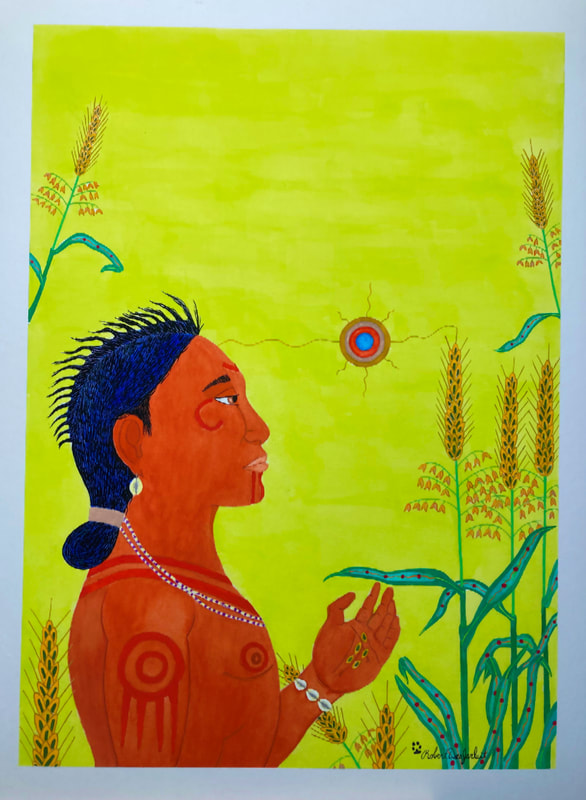

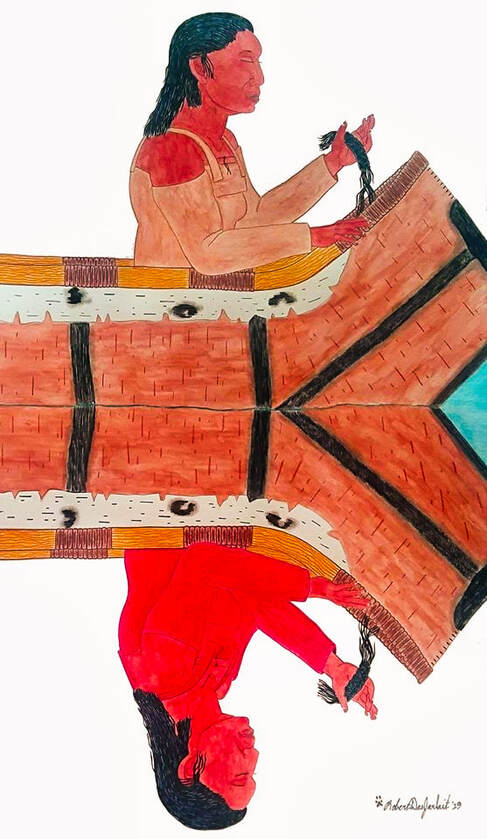

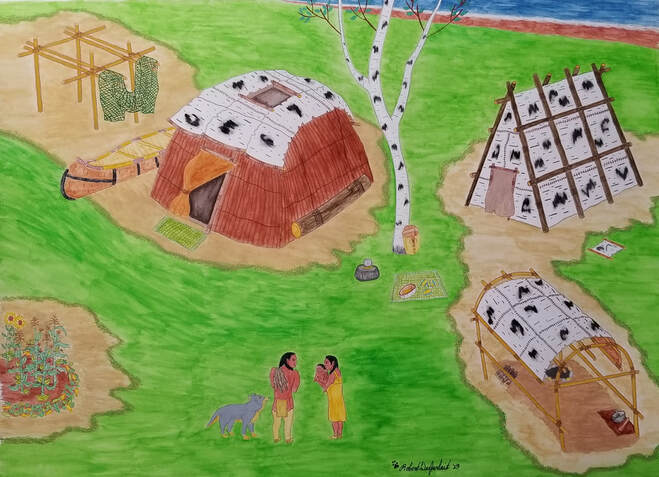

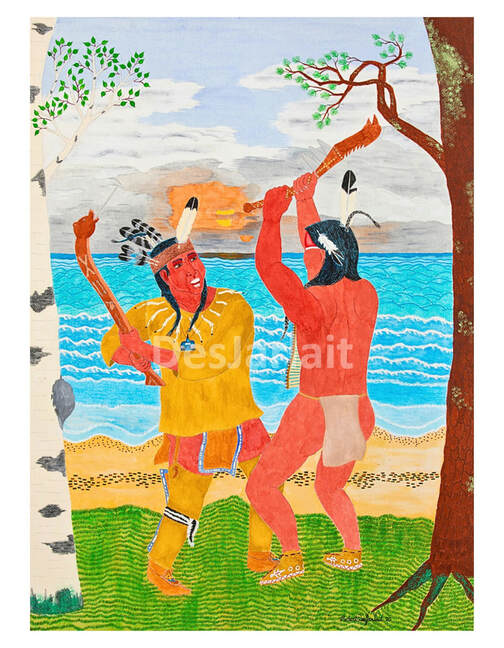

15" x 20" $1,000 Date of Completion / May 2022 This is my new work for 2022. With the exception of the last one, all are available for sale. The only criteria is purchased work be available for my solo exhibition at East Central Regional Arts Gallery at Hinckley MN. The exhibition will be Fall 2022 or early Spring 2023. Contact me at: [email protected] Ojibwe Mitigwaki Niimid (Ojibwe Woodland Dancers) 24" x 33" Gouache (Opaque Watercolor) Watercolor Board Private Collection Artistic Excellence Award / East Central Regional Arts Council 2022 IMAGE Art Show Ojibwe Mitigwaki Nimiid (Ojibwe Woodland Dancer) 20" x 30" Gouache Opaque Watercolor) Watercolor Board Private Collection Vietnam Ogichidaa - Ogichidaa Niimi (Vietnam Warrior - Veterans Dance) 22 1/2" x 30" Gouache (Opaque Watercolor) Watercolor Paper University of Minnesota / Morris Campus Collection Nibi (Water) 16" x 24" Gouache (Opaque Watercolor) Watercolor Board $1100 Giwiiwizens Nagamo Misko-Magoodaas (Boy Singing the Red Dress Song) 15" x 20" Gouache (Opaque Watercolor) Watercolor Board $1000 Nanabozho miinawaa Manoomin (Nanabozho and Wild Rice) 15" x 20" Gouache (Opaque Watercolor) Watercolor Board University of Minnesota / Morris Campus Collection Bawaajigan Wanashkid (Tailfeather Woman) 15" x 20" Gouache (Opaque Watercolor) Watercolor Board $950 Ziibaaska'igan Bawaajigan

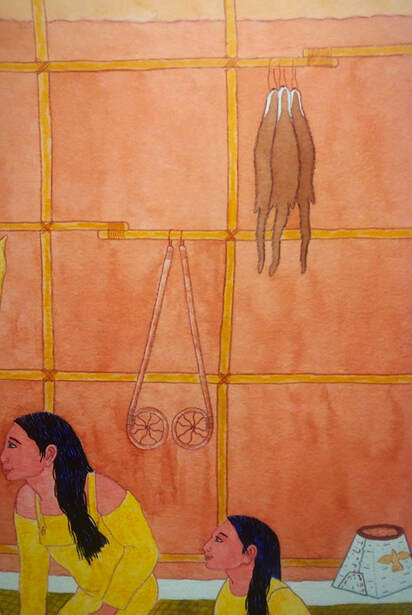

(Vision of the Jingle Dress) 15" x 20" Gouache (Opaque Watercolor) Watercolor Board Private Collection Some of the following works are for sale. For inquiries contact me at [email protected] Misko Magoodaas (Red Dress) Watercolor / Gouache / 13” x 22” 2019 $1200 Nagamon Bimaadiziwin (Song of Life) 2020 Watercolor (Opaque) / 22" x 30" East Central Regional Arts Council Gallery Collection Ma'iingun Ogichidaa (Wolf Warrior) Watercolor/ Watercolor Pencil / 24" x 18" 2019 Private Collection Mandidoo'ikwe Zaaga'igan (Spirit Woman of the Lake) Watercolor (Opaque) / 18" x 25" 2020 Private Collection Aadizookewinini (Storyteller) Watercolor (Opaque) / 19" x 27" 2019 Private Collection Maamiikwendamaw Nagawbow Remembrance - Boy in the Woods - Patrick Robert DesJarlait Watercolor / 18" x 25" 2019 Private Collection Aadizookaan Makizin-Ataagewin (Origin of the Moccasin Game) Watercolor/ 15" x 19 1/2" 2019 Private Collection Gashkibidaagan Ikwe (Bandolier Bag Woman) Watercolor / Gouache / 14” x 12” 2019 $950 Dakobijigan (Tied Rice) Watercolor / Gouache / 12” x 15” 2019 Private Collection Manidookewin (Ceremony) Watercolor / 16" x 11" 2019 Private Collection Abagwe’ashk Akwe (Cattail Woman) Watercolor / 14 1/2" x 13" 2019 Private Collection Doodoo miinawaa Abinoojiinh (Mother and Child) Watercolor / 14 1/2" x 15" 2019 Private Collection Giiwosewinini (The Hunter) Watercolor / Gouache / 21” x 15” 2019 $1200 Niibinishi Gabeshi (Summer Camp) Watercolor / Gouache / 21” x 16” 2019 $1200 Binawiigo (In the Beginning) Watercolor / Gouache / 15” x 11” 2019 $950 Miigaadiwining Wayekwaadaawangaa-ziibi (Battle at Sandy) Watercolor / Gouache / 22” x 30” 2020 Private Collection Wiizhaandige Gitigaan (Unfinished Garden) Self Portrait Watercolor / 16" x 17" 2019 NFS Mitigwaakokwi Inoodewiziwin (Woodland Family) Gouache / 18" x 24" 2019 Private Collection Gidagaabinesh (Spotted Bird) Colored Pencil / 18" x 24" 2018 Private Collection Aazha miinawaa Manidoo-Giizhikens

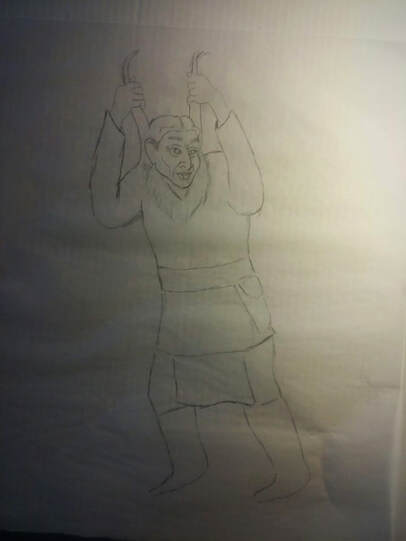

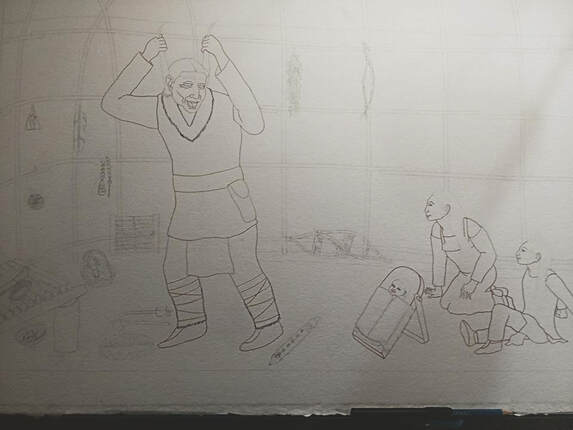

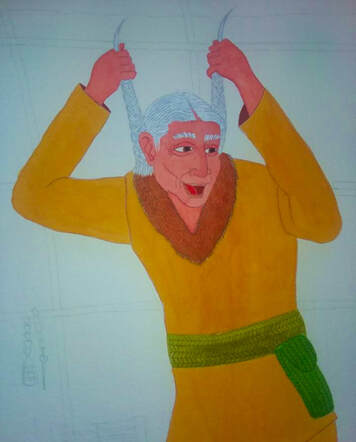

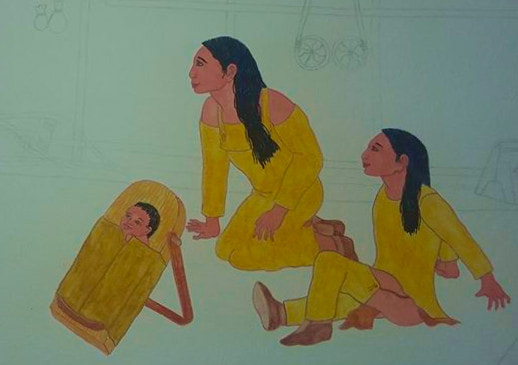

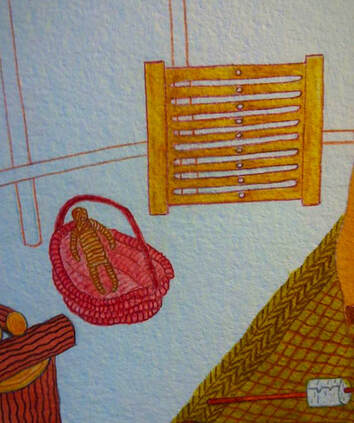

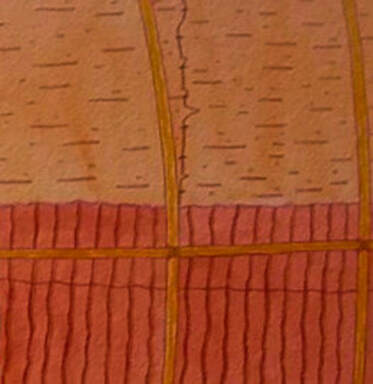

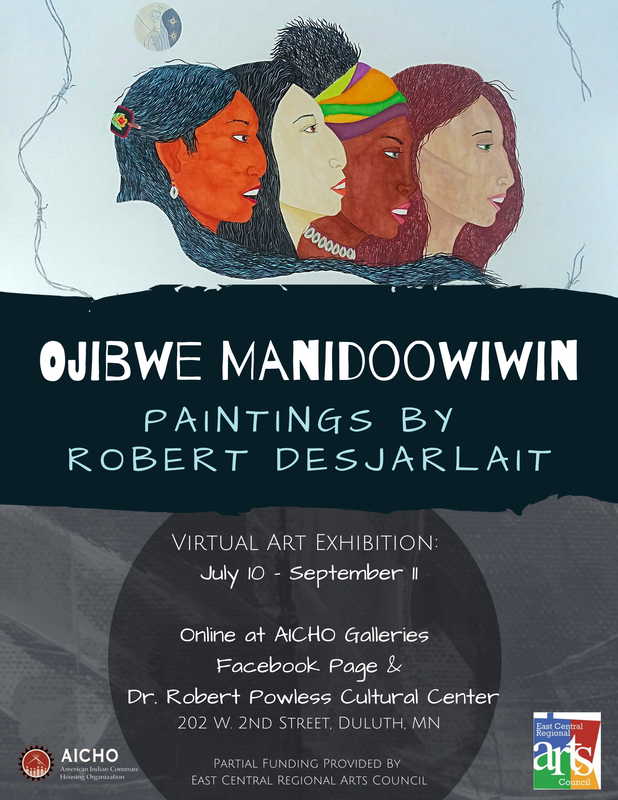

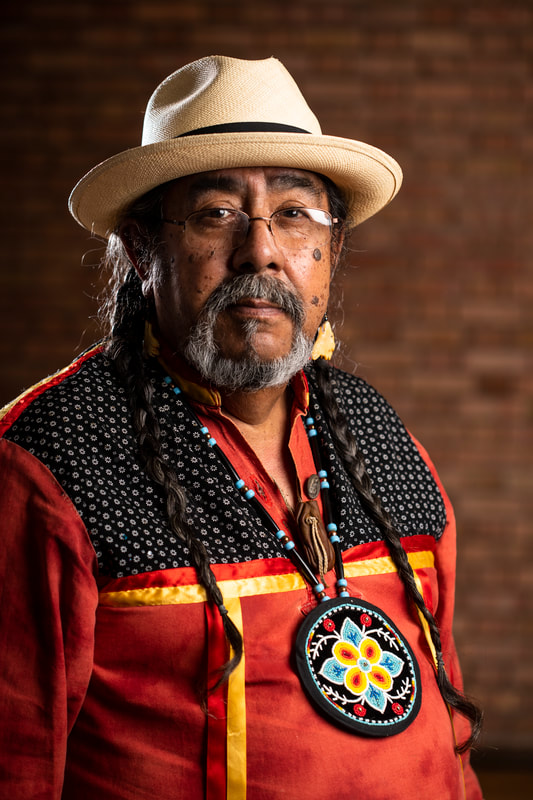

(Aazha and the Spirit Tree) Colored Pencil / 18" x 24" 2018 Private Collection In conjunction with my current solo exhibition (“Ojibwe Manidoowiwin,” AICHO Gallery, July 11-Sept 10), I’ll be writing a few articles related to the art. This first article focuses on the process of making art – some of my concepts regarding my art and looking at one of my works - from initial sketches to the finished work. Concepts and Visions I’ve written elsewhere about the meaning of Ojibwe Manidoowiwin. Ojibwe Spirit, i.e., Ojibwe Manidoowiwin, is based on Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious (kollektives Unbewusstes). Jung wrote: “And the essential thing, psychologically, is that in dreams, fantasies, and other exceptional states of mind the most far-fetched mythological motifs and symbols can appear autochthonously at any time, often, apparently, as the result of particular influences, traditions, and excitations working on the individual, but more often without any sign of them. These "primordial images" or "archetypes," as I have called them, belong to the basic stock of the unconscious psyche and cannot be explained as personal acquisitions. Together they make up that psychic stratum which has been called the collective unconscious. “The existence of the collective unconscious means that individual consciousness is anything but a tabula rasa and is not immune to predetermining influences. On the contrary, it is in the highest degree influenced by inherited presuppositions, quite apart from the unavoidable influences exerted upon it by the environment. The collective unconscious comprises in itself the psychic life of our ancestors right back to the earliest beginnings. It is the matrix of all conscious psychic occurrences, and hence it exerts an influence that compromises the freedom of consciousness in the highest degree, since it is continually striving to lead all conscious processes back into the old paths.” Ojibwe Manidoowiwin is, essentially, the Ojibwe collective unconscious. In terms of art, imagery is formed by tribal primordial images or archetypes. My art is but one aspect of Ojibwe Manidoowiwin. Visual arts, beadwork, quillwork, sculpting, carving and other art expressions are facets of Ojibwe Manidoowiwin. On another note, I can’t speak for all mazinibiigewininiwag (artists), however I think that most mazinibiigewininiwag, in particular those who have been doing art for a number of years, develop philosophies/concepts about what their art is about. It is the concept that sustains the artist in the creation of their art. The subject matter may vary, but there is a unifying concept that brings the imagery together. Art incorporates an artist’s concept of their art – what it’s about; the process expresses the concept through the painted imagery. However, an artist doesn’t sit before a canvas and consciously think about how s/he is going to express their concept. Rather, the concept is inherent within the artist and the art expresses an innate spontaneity of concept. But the concept isn’t necessarily static. Spontaneity allows for changes. Hence, the concept evolves yet remains rooted in the central core of the artist’s intuitive notion of her/his creativity. Another level of creating art is izhinamowin – vision. It may be a complete vision –Waaseyaabindamowin – in which the imagery is perspicuous when the artist begins his/her work. Or, it may be bawewin(an) – imagery revealed in a dream or several dreams. Sometimes it’s a combination of the two. The vision may be complete, yet bits and pieces may be revealed through dreams and waking visions as the artist creates her/his work. This is part of the spontaneity of concept. Essentially, a visual work is the fulfillment of the artist’s vision. Titles in Ojibwe When I first began doing my art, a number of pieces were titled in Ojibwe. Out of the 31 works in my first solo exhibit (1986), 16 were titled in Ojibwe. At that time, I knew very little about the language. What was the impetus for using Ojibwe titles? I wasn’t influenced by other Ojibwe artists. As far as I knew, other artists weren’t using Ojibwemowin. In the 1980s, language was stagnant. There weren’t any language programs. The Baraga dictionary and Nichols and Nyholm Word List book were the only sources for Ojibwe words. Albeit the language earning was limited, I had access to words. Using words for titles wasn’t simply because I wanted my art to be more “Ojibwe.” It had to do with the changes I was going through in my life. In 1982, I stopped drinking. Sobriety opened the door to engage in art. My sobriety marked a new life. It allowed me the opportunity to learn about traditional values and practices. The words, terms, and phrases of language enabled me to see the world through an Anishinaabe mindset. Ojibwemowin helped to give my world shape and form. It gave, and continues to give, shape and form to my art. N. Scott Momaday wrote: “A word has power in and of itself. It comes from nothing into sound and meaning; it gives origin to all things…We perceive existence by means of words and names. To this or that vague, potential thing I will give a name, and it will exist thereafter, and its existence will be clearly perceived. The name enables me to see it. I can call it by its name, and I can see it for what it is.” To name something in one’s language gives the word power. Words are medicine. Words can hurt or they can help. Words can heal. Every word has a spiritual meaning behind it. It is the spirit of the word where the power comes from. Each word is a spiritual instruction to Gichi-Manidoo, the Creator. Each word or phrase is a prayer and a request. When we say the word or in our thoughts, we are making a request. Gichi-Manidoo responds. We need to be aware of what we are asking for and to understand the relationship between the word and the spiritual instruction behind it. In relation to art, naming a work in Ojibwe gives it power. It gives origin to the images that I paint. It also provides an educational value. The viewer learns something about the language. In this regard, it keeps the language alive. Ma’iingan signature One of the distinguishing features in my art is my signature. I sign my name with the image of a ma’iingan (wolf) paw. I’ve always signed my work with a ma’iingan paw going back to my first artwork in 1983. I quit drinking in 1982. During that time, I had several lucid dreams. A recurrent dream was about a ma’iingan. It always seemed that the ma’iingan was trying to tell me something. But the meaning only became clear after several dreams. At first, the ma’iingan was alone. He wandered through the woods, curious and looking, observing the life around him – the plants, trees, waters, animals, and insects. He could have very well been the ma’iingan that journeyed with Anishinaaba – Original Man – companions who were separated by Gichi Manidoo to live their own lives when the Earth was new. In the dreams, he found a new companion, a female ma’iingan, with whom he fathered four cubs. Together, they lived in the forest and he became their protector. I related the dreams to my own life. Like ma’iingan, I journeyed alone. Then I met my companion. We didn’t have children during the time I had the dreams. But the dreams foretold that we would have four children. And in my role as a father, I would, like the dream ma’iingan, be the protector of my family. The ma’iingan is akin to a bawaagan (guardian spirit animal). In my new life as a young husband and a father-to-be in the near future, the ma’iingan bawaagan provided me with a sense of direction and guidance. And, it is for this reason, why I sign my name with the paw of a ma’iingan. Aadizookewinini (Storyteller) Aadizookewinini (Storyteller), 22" x 30," Watercolor/Gouache, 2020 This is my first sketch of the storyteller. I always sketch on tracing paper. Tracing paper allows me to flip the paper and see if the proportions are correct and make corrections (on both sides of the paper) if needed. Basically, the original sketch is reworked and becomes the final sketch. Details such as hair, fur, belt, pouch, etc. are added once I begin to paint the figure. I did the sketch of the children's group on a separate sheet of tracing paper to allow for positioning. At this point, I've moved from tracing paper to the medium for the painting - a 30" x 22" cold press, watercolor sheet of 300 lbs paper. I moved the dikinaagan (cradle board) to the front of the two children. I sketched in several of the items that are inside the wiigiwam. One of the things I wanted to emphasize in this painting was the inside of a wiigiwam (birch bark lodge).They were built to accommodate the size of the family. As such, they could be fairly spacious and allowed for items to be stored on the walls and the perimeter of the walls. Although it's nor depicted, a hearth is located at the center of the lodge. The first image I paint is the storyteller. The central figure is always first when I paint. I mix my skin tone and paint his face and hands. For consistency, I cover and save the skin tone paint for the children. After painting in the skin tone, I work my way down beginning with the hair, then fur collar, shirt, leggings, and apron, biboon-makizin (winter boots); the last thing I paint is the waasechiganaatig (sash) and biindaagan (pouch) that are made from reeds. After finishing the storyteller, I paint the group of children. I do all the skin tones first. Then I do the young boy, followed by the girl. The baby and cradle board is last. To complete the storyteller, I painted the items he uses to tell his stories. This detail shows his dewe'igan (hand drum), deyewe'iged (drum stick), and zhina'oojigan (rattle). Detail of storyteller's bibigwan (flute). To complete the central figures (storyteller and children), I paint the gaasiizideshimowin (floor mat). The next step is painting the desa'on (lodge platform), followed by the opwaagan (pipe), mishiikewi-dashwaa (turtle shell), and bagesewinaagan (dish game). Detail of oziisigobimizhii-makak (willow basket), asigobaani-mazinichigan (basswood bark doll), and okaadeniganaatig (loom - this particular loom is an Ojibwe heddle loom used to weave sections for reed mats) My next step is to paint the interior of the wiigiwam - abanzhiiwaatigoon (lodge poles), wiigwaasabakwaan (birch bark roof) and aasamaatigoon (inside walls). Detail - asabikeshiinh (dream catcher), bigiiwizigan (maple sugar taffy/candy), nabaa'waaganag (ring and toss game), giniw-miigwan (golden eagle feather). Detail - aagimaakwan (snow shoes), gamaagiwebiinigewin (snow snake game), wiingashk (sweetgrass), mashkodedewashk (sage). Detail - baaga'adowaanan (lacrosse sticks), nigigwayaanag (otter hides), and makak (birch bark container). Art and Text © 2020, Robert DesJarlait July 8, 2020 Contact: Ivy Vainio American Indian Community Housing Organization (AICHO) 218-722-7225 | [email protected] Artist: Robert DesJarlait 218-380-8491 [email protected] AICHO Galleries to Host Virtual Art Exhibition with Red Lake Nation Artist Robert DesJarlait Robert DesJarlait, Red Lake Nation Ojibwe tribal member and long time established artist, will show a collection of his recent watercolor/mixed media paintings along with a series of retrospective work from the 1980s in a virtual exhibition entitled, “Ojibwe Manidoowiwin” from July 10 - September 11. His works will be displayed in the Dr. Robert Powless Cultural Center Gallery. However, his work will be showcased online on the AICHO Galleries Facebook event page under the same name as the Exhibition for greater access for the public to view. There will also be an online recorded Artist Talk, date and time to be announced. A majority of his work is for sale. Artist’s Statement: As an artist, I paint what gives meaning to me as an individual. I look at my art from a tribal perspective. Through my art, I visualize a particular facet of Ojibwe experience. My paintings are personal visions of a tribal past. The imagery composes a micro/macro-scopic Ojibwe universe. Interwoven in this universe are creation stories, history, customs and traditions, and my central theme – Ojibwe Manidoowiwin, the tribal spirit of the Ojibwe people. Artist Bio: Robert DesJarlait (Endaso-Giizhik) is from Miskwaagamiiwi-zaaga’igan (Red Lake). He belongs to Makwa Doodem (Bear Clan). He is an artist, writer, and traditional dancer. He began his career as a fine artist in 1983. He is also an illustrator and muralist. He currently lives in Onamia, MN with his wife and daughter. To view his artwork from last year’s exhibition at the Two Rivers Gallery in Minneapols: http://thecirclenews.org/the-arts/ojibwe-artist-robert-desjarlait-reemerges-as-artistic-force/ Recognition to the McKnight Foundation, the Bush Foundation and the East Central Regioinal Arts Council for funding towards this art exhibition. Robert is willing to speak to the media about his work and this show. See contact details at the beginning of the media release. Wiizhaandige Gitigaan (Unfinished Garden) / Self-Portrait, 2019 Note: Article originally published on IHadCancer, August 2019 By Robert DesJarlait One day, the Earth was submerged by a destructive flood sent by Mishibijiw, the Great Underwater Serpent. Nenabozho, our Great Uncle, survived. Drifting on a log, he obtained pebbles of dirt from the muskrat. After planting the dirt on his log, the Earth regrew and new life reemerged from the life that existed before.” In April 2013, I heard the three words that you don’t want to hear – you have cancer. I thought my life was over. I was 66 years old, retired, and at that point in my life, art was far from my mind. One day, I took a walk in the halls of the cancer ward with my IV stand rolling beside me. My prognosis was good. Following surgery for the removal of my ascending colon, my cancer was classified as Stage I meaning the cancer hadn’t metastasized and chemo wasn’t required. As I walked along the hallways of the cancer ward, I saw walls covered in art. I had no idea who the artists were. I asked a nurse: “Who are the artists?” She replied that some of them were by former cancer patients and others were from families who had lost a loved one to the disease. And, therein, a seed was sown and a promise made that someday I would return with a painting to join the walls of art in the cancer ward. But any aspirations of returning to art came to a jolting halt in May 2016. My annual CT scan revealed a lesion on the left lobe of my liver. This time around, my surgery was preceded by four rounds of neoadjuvant chemo and followed by twelve rounds of adjuvant chemo. As a result of my recurrence, I became a Stage IV cancer survivor. In November 2018, Reemergence became a part of my cancer journey. Cancer survivors live a cautiously optimistic life. We really can’t look too far into the future. Goals and priorities need to be in the short term. The ideas that floated through my mind in the cancer ward came to fruition. But it was really a question of whether I could return, or more specifically reemerge, to the fine art form I established in the 1980s. “Gidagaabinesh” (Spotted Bird) was the first work and a tribute to Herb Sam, one of my spiritual mentors and advisors who passed from liver cancer in September 2018. I didn’t have watercolors or brushes, so I decided to use colored pencils and, for the first time, watercolor pencils. I decided to do the work encompassed in a circle – the circle was a hallmark of my illustration art in the 1990s and early 2000s. “Gidagaabinesh” was a test of sorts. Did I retain my skills as a fine artist after a nearly 35 year absence? Or had my abilities diminished? With the finished work, I found that my palette hadn’t lessened and my aesthetics had matured. Indeed, rather than being diminished, they had improved. It was almost as if they had been in limbo and waited for the reopening of the channels to my creativity. I did a sister piece - “Aazha miinawaa Manidoo-Giizhikens” (Aazha and the Spirit Tree) with two main characters from a children’s book I’m writing about two Ojibwe children with childhood cancers. Manidoo-Giizhikens (the Spirit Tree) has a special place in my heart following a photo shoot there in 2016 with well-known photographer Ivy Vainio. After completing the two works, I decided to create a body of work called Reemergence. From late November to late January, I worked on a number of pencil studies that would form the series. The art largely reflected the themes I developed in the 1980s – scenes of the traditional, everyday roles of Ojibwe-Anishinaabe women and men in the 1700s-1800s. In mid-March, I obtained watercolors, gouache (a new medium for me), and brushes, and began working on the paintings. By mid-June, I completed 15 paintings for a total of 17 works for the Reemergence series. The title reflects my reemergence as a fine artist. But it also reflects my reemergence after battling cancer for seven years. Reemergence is not cancer art per se; rather, it’s art by a cancer survivor who is Ojibwe-Anishinaabe who is an artist. The art is a paradigm of creativity and healing in a time of sickness. However, Reemergence has a deeper meaning. In a cultural context, Nenabozho’s story has a metaphorical meaning in relation to my cancer experience. Cancer and Mishibijiw are interrelated as malevolent beings that bring death, chaos, and destruction. The log is my physical body and Nenabozho represents my spirit. The pebbles of dirt are the medicines that help heal me. And, forthwith, a new life reemerges from the life that existed before. Our elders teach that our personal lives move in a circle. We always come back to a point that we’ve left behind. We may bypass the point and move on. Or we may stop at the point and find something that provides a deeper meaning and direction on our path. With Reemergence, I’ve reached such a point. © Robert DesJarlait, 2019

By Robert DesJarlait It would be simple to say that the Anishinaabe place in contemporary visual art began with Patrick DesJarlait and George Morrison and everything fell into place after that. But the history of Anishinaabe art is much more complex than a simplification. Placing Anishinaabe art within a specific period, e.g., contemporary, overlooks the evolution and history of Anishinaabe art. The ethnocentric perspective of Native America art history establishes labels and categories – applied art, handicrafts, decorative arts, fine art, and visual art. But from a Native American worldview, there are no borders or boundaries. Melville Herskovits writes: “Our [Western] fixation on pseudo-realism contained a hidden, culture-bound judgment wherein the values of our own society, based on our particular perceptual modes, were extended into universals and applied to art in general…The ‘natural’ world is natural because we define it as such because most of us, immersed in our own culture, have never experienced any other definition of reality.”[1] Herskovits was writing about the Euro-American perspective regarding “primitive art.” The notion of early Native art as being primitive, at least according to European standards, was established by anthropologists. Native art was considered crude and childlike. As such, it lacked aesthetic value and was purely a functional and utilitarian art. Hence, the boundary was set between Native American, African, and Oceanic indigenous art and the aesthetics of European art. Wolfgang Haberland further defines the differentiation of aesthetics: “There are several kinds of aesthetics…‘Universal aesthetics’ embraces the general human ability to create and appreciate objects of beauty. ‘Group aesthetics’ embodies a given culture’s ideas about beauty. It is shared by all or most members of the group…‘Individual’ aesthetics refers to the individual ability to appreciate, or, in the case of an artist, to create beauty.”[2] Haberland adds: “Anthropologists, art historians, and art critics interested in non-Western art are always trying to explain foreign group aesthetics through European-formed views of individual aesthetics.”[3] And therein lays the crux of the problem of defining Native art. Compartmentalized, categorized, and labeled, the interconnectedness of Native art and its inherent aesthetics are disconnected. In the ethnocentric perspective, artist and art become maker and object. The finger strokes on a rock are not connected to a paint brush on canvas. To understand Anishinaabe art, one needs to set aside labels, such as “contemporary,” and view Anishinaabe aesthetics from an Anishinaabe worldview. In this worldview, there is no separation between art forms; rather there is a continuity of aesthetics, although the medium differentiates the application and expression of those aesthetics. It should be noted that Anishinaabe art is representative of the art forms and aesthetics that evolved among indigenous peoples in North America. In this regard, Anishinaabe art is a microcosm of the macrocosm of Native American art. In Minnesota, the oldest forms of the Anishinaabeg art are found on rock faces in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area and Lake Superior National Forest and extend into Quetico Provincial Park in Canada. Dating ranges from 1000-1500 AD. Pictographs are defined as images painted or etched on rock. However, Anishinaabe writer Gerald Vizenor provides a more expressive, worldview definition – pictomyth: the believable Anishinaabe pictures of myths or believable Anishinaabe myths of pictures.[4] Vizenor’s definition correlates to A. Irving Hallowell’s study of Anishinaabe people and “other than human persons” and the relationship to stories: “Ojibwa myths are considered to be true stories, not fiction.”[5] In this view, pictomyths are the representation of the imagery of dreams and visions that formed the basis of origin stories. Pictomyths are true in the sense they are not fanciful representations of tribal myths; rather, they represent the reality and experiences of the artist in the real world. The individual aesthetics of painted rock imagery was more focused on content than form. But the forms were interrelated to a group aesthetics as evidenced by the pictomyths etched on birch bark scrolls. The differentiation between the two was media, medium, and technique. The rock pictomyths were painted with red ochres composed of iron-stained earths. According to Northern Anishinaabe artist Norval Morrisseau, the red earths used for paint resulted from a battle between two thunderbirds. The blood from the battle rained upon the earth turning the sands red. This particular sand was, in the Anishinabe language, called onaman.[6] The binding agent for onaman was fish glues or egg fluid, or bear grease. Although brushes with moose hair bristles were employed, many pictomyths were painted by finger. Selwyn Dewdney writes: “[T]he artist’s preference [was] for a vertical rock face close to the water. The sites themselves show a bewildering variety of locations…there are groups of obviously related material that form compact, well-designed compositions…[and] instances where the natural flaws of the surface are incorporated into the whole concept.”[7] Dewdney categorized pictomyths into several groups: animal, birds, mythological creatures, hands, other human subject matter, man-made objects, and, the largest group, unidentified abstract symbols. Overall, the rock pictomyths focused on the relationship between humans and the aadisookaanag, i.e., other than human persons: the Four Winds, Sun, Moon, Thunderbirds, “owners” or “masters” of species of plants and animals and the characters in myths – collectively spoken of as “our grandfathers” or ancestors.[8] Like the individual aesthetics with its focus on content rather than form on rock pictomyths, the development of birch bark pictomyths expressed a group aesthetics that was cultural in form yet emphasized content. Birch bark pictomyths were a cultural mode of communicating and recording history, migration, ceremonies, traditions, stories, and songs. Hence, Anishinaabe art, in its earliest forms, was a means of communication. The form itself conveyed the message. However, the imagery of the form expressed a group aesthetic. That is to say, the designs were specifically Anishinaabe and the use of these designs extended beyond birch bark pictomyths and were used by the tribal whole. Wooden spoons, ladles, and bowls, birch bark containers, woven reed mats, yarn bags and sashes, moccasins and clothing were decorated with pictomyths. As such, Anishinaabe images had a decorative, i.e., aesthetic, intent and the creation of such imagery was largely the work of women. The techniques varied greatly. Etchings on wood, plaiting on wicker baskets, drawing and cutouts on birch bark baskets. The imagery reflected the aesthetics of the rock paintings and birch bark scrolls. Art by men was largely confined to carving and sculpturing. This included wooden spoons, ladles, bowls, cradleboards, war clubs and pipes. The sculpturing on pipes, war clubs, and figurines were three-dimensional human and animals figures based on pictomyth imagery. The main form of expressive art was through quillwork and, to a lesser extent, animal hairs. Dyes were obtained from barks, roots, leaves, flowers, and berries and used to color quills and animal hairs, including various fibers. Geometric quilled images depicted the individual’s clan affiliation and dream symbols. Abstracted motifs of animals, flowers, insects, and leaves were common in quillwork. Quillwork tended toward abstraction because of the rigidly of the quills. However, Carrie Lyford noted: “The Ojibwa introduced the curvilinear pattern into the western region adopting and embellishing it to their fancy.”[9] From the curvilinear pattern, Anishinaabe artists developed a symmetrical double curve motif that curved out from a central point. The opposing curves were decorated with leaves, buds, and flowers that were also arranged symmetrically. With the introduction of the fur trade, broadcloth, blankets, yarns, ribbon, and beads provided new media and mediums to express group and individual aesthetics. Lois Jacka writes: “As skills were passed down through the ages, new materials became available, new techniques developed, and each succeeding generation contributed its own interpretations and innovations.”[12] Bands on woven bags featured diamonds, hour glasses, zigzags, and hexagons. Narrow bands included thunderbirds, underground panthers, deer, butterflies, dragonflies, and otter tracks. Lyford writes: “The Ojibwa laboriously frayed out woolen blankets…respun the wool, and redyed it…Native dyes were used to color the commercial yarns…later, colored commercial twine and yarns and commercial dyes were introduced.”[10] Ribbons in bright colors were used in appliqué border designs with various geometric motifs. Graceful curvilinear floral patterns were later developed and used as borders on robes, leggings, and breechcloths, on binding bands of cradle boards, and on the cuffs and front pieces of moccasins.[11] Like the double curve of the pre-contact period, floral designs were arranged symmetrically in appliqué work. The most significant media introduced to Anishinaabe artists in the contact era was trade beads. Whereas quillwork was the media for the depiction of group aesthetics in the pre-contact period, beads all but replaced quills as the new media. This new media provided for a fuller expression of individual aesthetics for Anishinaabe artists. Two techniques were employed in the application of beadwork. Bead weaving was done on a loom and bead embroidery was applied directly on broadcloth or velvet. On breechcloths, the design was symmetrical. On leggings, the pattern was asymmetrical, although the design on the left leg matched the design on the right leg. On vests, the front panels followed the same pattern as leggings. The asymmetrical pattern on the left side matched the pattern on the right side. On the back of the vest, the pattern was symmetrical. The most elaborate beadwork was the ceremonial (bandolier) bags worn by men. The large beadwork front piece panel and strap panels were woven on looms or embroidered on fabric. The patterns on the panels were usually asymmetrical and featured floral motifs or geometrical motifs. Making bandolier bags was the providence of Anishinaabe women. In the post-contact era, the impact of reservations and boarding schools led to a diminishment of tribal art. Ethnocide, linguicide, historical trauma/intergenerational trauma, and the imposition of Christian values and incorporation of Euro-American political structures affected all levels of Anishinaabe life. In art, the vitality of group and individual aesthetics became limited to the Anishinaabewishimo, i.e., the powwow. Many of the Bwaanzhiiwi`onan (dance outfits) worn by dancers maintained floral patterns and designs passed down generationally to families. Additionally, beaded items were sold through the tourist market. Such items were bought by collectors and museums. It was during this later period that “new materials became available [and] new techniques developed” [12] and opened a new area of expression in Anishinaabe art – the visual arts. The works of Patrick Robert DesJarlait (1921-1972) and George Morrison (1919-2000) created an alternative modernism and embodied deeply felt connections to the specific geography of northern Minnesota and to their identities as Anishinaabe artists.[13] Bill Anthes writes: “DesJarlait and Morrison maintained powerful connections to Red Lake and Grand Portage, where their people had lived for generations…their modern lives led DesJarlait and Morrison away from their reservations to discover their artistic vision in the larger world – their traditional homelands became in their art an essential resource for both artists.”[14] Visual arts itself is a misleading term since such art extends beyond the paintings of DesJarlait and Morrison, and the Woodland Art Movement established by Norval Morrisseau. Anishinaabe visual arts includes the contemporary work of artists whose media and aesthetics focuses on quillwork, beadwork, and appliqué work. These artists provide continuity to the aesthetics and motifs connected to the past, and have revitalized Woodland styles in clothing and accoutrements. In this regard, Anishinaabe art is worn and expresses the cultural identity of the wearer. The main connection between contemporary Anishinaabe artists of today is, obviously, their Anishinaabe descendency. Their art expresses their heritage and history. As such, their art conveys an evolving individual aesthetic that is rooted in the art of the traditional past. Works Cited

© All Rights Reserved, Robert DesJarlait, 2017

Note: Originally published in the Washington Post on 4/29/2020

Robert DesJarlait is an artist and writer. He is from the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation in northern Minnesota. She was never a stereotype. That was my thought earlier this month when I heard that “Mia,” as the Land O’Lakes Native American maiden was known, had been taken off the butter box. She was gone, vanished, missing. I knew Mia had devolved into a stereotype in many people’s minds. But it was the stereotype some saw that bothered me. North Dakota state Rep. Ruth Buffalo (D), for instance, told the Pioneer Press in St. Paul, Minn., that the Land O’Lakes image of Mia went “hand-in-hand with human and sex trafficking of our women and girls … by depicting Native women as sex objects.” Others similarly welcomed the company’s removal of the “butter maiden” was long overdue. How did Mia go from being a demur Native American woman on a lakeshore to a sex object tied to the trafficking of native women? I know the meaning of stereotypes. I participated in protests against mascots and logos using American Indian images in the early 1990s, including outside the Metrodome in Minneapolis when Washington’s team played the Buffalo Bills in the 1992 Super Bowl. In 1993, I wrote a booklet for the Anoka-Hennepin Indian Education Program about these stereotypes. Mia was originally created for Land O’Lakes packaging in 1928. In 1939, she was redesigned as a native maiden kneeling in a farm field holding a butter box. In 1954, my father, Patrick DesJarlait, redesigned the image again. My father had been interested in art since boyhood, when he drew images related to his Ojibwe culture. After leaving Pipestone boarding school in Minnesota in 1942, he joined the Navy and was assigned to San Diego, where he worked alongside animation artists from MGM and Walt Disney producing brochures and films for the war effort. In 1946, he established himself as one of the first modernists in American Indian fine art. After I was born in 1946, my family moved from Red Lake, Minn., to Minneapolis, where my father broke racial barriers by establishing himself as an American Indian commercial artist in an art world dominated by white executives and artists. In addition to the Mia redesign, his many projects included creating the Hamm’s Beer bear. By often working with Native American imagery, he maintained a connection to his identity. I was 8 years old when I met Mia. My father often brought his work home, and Mia was one of many commercial-art images I saw him work on in his studio. With the redesign, my father made Mia’s Native American connections more specific. He changed the beadwork designs on her dress by adding floral motifs that are common in Ojibwe art. He added two points of wooded shoreline to the lake that had often been depicted in the image’s background. It was a place any Red Lake tribal citizen would recognize as the Narrows, where Lower Red Lake and Upper Red Lake meet. In my education booklet, “Rethinking Stereotypes,” I noted that communicating misinformation is an underlying function of stereotypes, including through visual images. One way that these images convey misinformation is in a passive, subliminal way that uses inaccurate depictions of tribal symbols, motifs, clothing and historical references. The other kind of stereotypical, misinforming imagery is more overt, with physical features caricatured and customs demeaned. “Through dominant language and art,” I wrote, “stereotypic imagery allows one to see, and believe, in an invented image, an invented race, based on generalizations.” I provided a number of examples. Mia wasn’t one of them. Not because she was part of my father’s legacy as a commercial artist and I didn’t want to offend him. Mia simply didn’t fit the parameters of a stereotype. Maybe that’s why many Native American women on social media have made it clear that they didn’t agree with those who viewed her as a romanticized and/or sexually objectified stereotype. Instead, Mia seems to have stirred a sense of remembrance and place, one that they found reassuring about their existence as Native American women. I don’t know why Land O’Lakes dropped Mia. In 2018, the company changed the image by cropping it to a head shot. That adjustment didn’t seem like a bow to culturally correct pressure. Perhaps her disappearance this year is about nothing more than chief executive Beth Ford’s explanation that Land O’Lakes is focusing on the company’s heritage as a farmer-owned cooperative founded in 1921. But questions remain. Mia’s vanishing has prompted a social media meme: “They Got Rid of The Indian and Kept the Land.” That isn’t too far from the truth. Mia, the stereotype that wasn’t, leaves behind a landscape voided of identity and history. For those of us who are American Indian, it’s a history that is all too familiar. |

AuthorRobert DesJarlait Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed